Plate 131

American Robin

The first land-bird seen by me, when I stepped upon the rugged shores of Labrador, was the Robin, and its joyful notes were the first that saluted my ear. Large patches of unmelted snow still dappled the surface of that wild country; and although vegetation was partially renewed, the chillness of the air was so peculiarly penetrating, that it brought to the mind a fearful anxiety for the future. The absence of trees, properly so called, the barren aspect of all around, the sombre mantle of the mountainous distance that hung along the horizon, excited the most melancholy feelings; and I could scarcely refrain from shedding tears when I heard the song of the Thrush, sent there as if to reconcile me to my situation. That song brought with it a thousand pleasing associations referring to the beloved land of my youth, and soon inspired me with resolution to persevere in my hazardous enterprise.

The traveller who, for the first time in his life, treads the wastes of Labrador, is apt to believe that what he has been told or read of it, must be at least in part true. So it was with me: I had conceived that I should meet with numberless Indians who would afford me much information respecting its rivers, lakes, and mountains, and who, like those of the far west, would assist me in procuring the objects of my search. But alas! how disappointed was I when, in rambling along three hundred miles of coast, I scarcely met with a single native Indian, and was assured that there were none in the interior. The few straggling parties that were seen by my companions or myself, consisted entirely of half-bred descendants of "the mountaineers;" and, as to Esquimaux, there were none on that side of the country. Rivers, such as the Natasguan, which on the maps are represented as of considerable length, degenerated into short, narrow, and shallow creeks. Scarcely any of its innumerable lakes exceeded in size what are called ponds in the Southern States; and, although many species of birds are plentiful, they are far less numerous than they were represented to us by the fishermen and others before we left Eastport. But our business at present is with the Robin, which greeted our arrival.

This bird breeds from North Carolina, on the eastern side of the Alleghany Mountains, to the 56th degree of north latitude, and perhaps still farther. On the western side of those mountains, it is found tolerably abundant, from the lower parts of Kentucky to Canada, at all times of the year; and, notwithstanding the snow and occasional severe winters of Massachusetts and Maine, flocks remain in those States the whole season. Thousands, however, migrate into Louisiana, the Floridas, Georgia, and the Carolinas, where, in winter, one cannot walk in any direction without meeting several of them. While at Fayetteville, in North Carolina, in October 1831, I found that the Robins had already arrived and joined those which breed there. The weather was still warm and beautiful, and the woods, in every direction, were alive with them, and echoed with their song. They reached Charleston by the end of that month. Their appearance in Louisiana seldom takes place before the middle of November. In all the Southern States, about that period, and indeed during the season, until they return in March, their presence is productive of a sort of jubilee among the gunners, and the havoc made among them with bows and arrows, blowpipes, guns, and traps of different sorts, is wonderful. Every gunner brings them home by bagsful, and the markets are supplied with them at a very cheap rate. Several persons may at this season stand round the foot of a tree loaded with berries, and shoot the greater part of the day, so fast do the flocks of Robins succeed each other. They are then fat and juicy, and afford excellent eating.

During the winter they feed on the berries and fruits of our woods, fields, gardens, and even of the ornamental trees of our cities and villages. The holly, the sweet-gum, the gall-berry, and the poke, are those which they first attack; but, as these fail, which is usually the case in January, they come nearer the towns and farm-houses, and feed voraciously on the caperia berry (Ilex caperia), the wild-orange berry (Prunus carolinianus), and the berries of the pride of India (Melia azedarach). With these they are often choked, so that they fall from the trees, and are easily caught. When they feed on the berries of the poke-plant, the rich crimson juices colour the stomach and flesh of these birds to such an extent as to render their appearance, when plucked, disagreeable; and although their flesh retains its usual savour, many persons decline eating them. During summer and spring they devour snails and worms, and at Labrador I saw some feeding on small shells, which they probed or broke with ease.

Toward the approach of spring they throw themselves upon the newly ploughed grounds, into the gardens, and the interior of woods, the undergrowth of which has been cleared of grass by fire, to pick up ground-worms, grubs, and other insects, on which, when perched, they descend in a pouncing manner, swallowing the prey in a moment, jerking their tail, beating their wings, and returning to their stations. They also now and then pick up the seed of the maize from the fields.

Whenever the sun shines warmly over the earth, the old males tune their pipe, and enliven the neighbourhood with their song. The young also begin to sing; and, before they depart for the east, they have all become musical. By the 10th of April, the Robins have reached the Middle Districts; the blossoms of the dogwood are then peeping forth in every part of the budding woods; the fragrant sassafras, the red flowers of the maple, and hundreds of other plants, have already banished the dismal appearance of winter. The snows are all melting away, and nature again, in all the beauty of spring, promises happiness and abundance to the whole animal creation. Then it is that the Robin, perched on a fence-stake, or the top of some detached tree of the field, gives vent to the warmth of his passion. His lays are modest, lively, and ofttimes of considerable power; and although his song cannot be compared with that of the Thrasher, its vivacity and simplicity never fail to fill the breast of the listener with pleasing sensations. Every one knows the Robin and his song. Excepting in the shooting season, he is cherished by old and young, and is protected by all with anxious care.

The nest of this bird is frequently placed on the horizontal branch of an apple-tree, sometimes in the same situation on a forest-tree; now and then it is found close to the house, and it is stated by NUTTALL that one was placed in the stern timbers of an unfinished vessel at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in which the carpenters were constantly at work. Another, adds this admirable writer, has been known to rebuild his nest within a few yards of the blacksmith's anvil. I discovered one near Great Egg Harbour, in the State of New Jersey, affixed to the cribbing-timbers of an unfinished well, seven or eight feet below the surface of the ground. To all Such situations this bird resorts, for the purpose of securing its eggs from the Cuckoo, which greedily sucks them. It is seldom indeed that children meddle with them.

Wherever it may happen to be placed, the nest is large and well secured. It is composed of dry leaves, grass, and moss, which are connected internally with a thick layer of mud and roots, lined with pieces of straw and fine grass, and occasionally a few feathers. The eggs are from four to six, of a beautiful bluish-green, without spots. Two broods are usually raised in a season.

The young are fed with anxious care by their tender parents, who, should one intrude upon them, boldly remonstrate, pass and repass by rapid divings, or, if moving along the branches, jerk their wings and tail violently, and sound a peculiar shrill note, evincing their anxiety and displeasure. Should you carry off their young, they follow you to a considerable distance, and are joined by other individuals of the species. The young, before they are fully fledged, often leave the nest to meet their parents, when coming home with a supply of food.

During the pairing season, the male pays his addresses to the female of his choice frequently on the ground, and with a fervour evincing the strongest attachment. I have often seen him, at the earliest dawn of a May morning, strutting around her with all the pomposity of a pigeon. Sometimes along a space of ten or twelve yards, he is seen with his tail fully spread, his wings shaking, and his throat inflated, running over the grass and brushing it, as it were, until he has neared his mate, when he moves round her several times without once rising from the ground. She then receives his caresses.

Many of these birds shew a marked partiality to the places they have chosen to breed in, and I have no doubt that many which escape death in the winter, return to those loved spots each succeeding spring.

The flight of the Robin is swift, at times greatly elevated and capable of being long sustained. During the periods of its migrations, which are irregular, depending upon the want of food or the severity of the weather, it moves in loose flocks over a space of several hundred miles at once, and at a considerable height. From time to time a few shrill notes are heard from different individuals in the flock. Should the weather be calm, their movements are continued during the night, and at such periods the whistling noise of their whigs is often heard. During heavy falls of snow and severe gales, they pitch towards the earth, or throw themselves into the woods, where they remain until the weather becomes more favourable. They not unfrequently disappear for several days from a place where they have been in thousands, and again visit it. In Massachusetts and Maine, many spend the most severe winters in the neighbourhood of warm springs and spongy low grounds sheltered from the north winds. In spring they return northward in pairs, the males having then become exceedingly irritable and pugnacious.

The gentle and lively disposition of the Robin when raised in the cage, and the simplicity of his song, of which he is very lavish in confinement, render him a special favourite in the Middle Districts, where he is as generally kept as the Mocking-bird is in the Southern States. It feeds on bread soaked in either milk or water, and on all kinds of fruit. Being equally fond of insects, it seizes on all that enter its prison. It will follow its owner, and come to his call, peck at his finger, or kiss his mouth, with seeming pleasure. It is a long-lived bird, and instances are reported of its having been kept for nearly twenty years. It suffers much in the moult, even in the wild state, and when in captivity loses nearly all its feathers at once.

The young obtain their full plumage by the first spring, being spotted on the breast, and otherwise marked, as in the plate. When in confinement they become darker and less brilliant in the colours, than when at liberty.

So much do certain notes of the Robin resemble those of the European Blackbird, that frequently while in England the cry of the latter, as it flew hurriedly off from a hedge-row, reminded me of that of the former when similarly surprised, and while in America the Robin has in the same manner recalled the Blackbird to my recollection.

The extent of migration of this bird, and its breeding from the Texas to the 56th degree of north latitude, and from the Atlantic coast to the Columbia river, seem to me to afford a strong argument against the necessity of migration in birds. In countries, like ours, of great extent and varied climate, migrating birds find many favourable places at which to stop during the summer months for the purpose of breeding. I have repeatedly mentioned that young birds regularly advance farther southward in winter than their parents, which may be accounted for by the capability of enduring cold being greater in the latter. Now, is it not probable that young birds of a second or third brood, which are urged at an earlier period than those of the first set, but late in the season, to force their way southward, and save themselves from the rigours of approaching winter, are at this period of weaker constitution than those which have been born earlier, and have been less pressed by time in prosecuting their journey southward? In consequence of this, the last young broods may be unwilling, perhaps unable, on the approach of spring, to start and follow their stronger companions to the land of their nativity. They may thus remain and breed in their first year's winter quarters, or advance so far as their strength will allow them. In the course of my studies, I have, in a great number of instances, observed that such birds as produced three broods in one season and in the same district, were all much older than those which produced only one brood. Of this any one can easily assure himself by shooting the breeding birds, and either bending or breaking their bones, or tearing asunder their pectoral muscles, which will be found harder or tougher in proportion to their age. Thus I am inclined to believe, that the farther south breeding individuals are found, the younger they are, and vice versa. This general rule is well exhibited in most of the species of birds, whether of the land or of the water, that are known to proceed in spring northward, and to return southward at the appearance of the inclement season; for in them the gradual progress of the young may easily be compared with the much slower advance of the old.

I have, on many occasions, when certain species returned to the nest or spot where they bred the previous season, observed, that what I considered to be the parents of the first year's young, were again the occupants. In the Swallow tribe, and in some of our travelling Woodpeckers, as well as in the Summer Duck, the Dusky Duck, the Mallard, the Hooded Merganser, Crow Blackbirds, Starlings, Kingfishers, Canada Geese, &c., this has proved correct, in as far as I could ascertain by the comparative softness of their bones and pectoral muscles. I think, further, that such species as merely enter the southern parts of our country in the breeding season, as the Mississippi Kites, Fork-tailed Hawks, Roseate Spoonbills, Flamingoes, Scarlet Ibises, &c. would all prove, if their winter retreats were well ascertained, to advance much farther southward than any of those which reach us first, and which continue their movements northward; with the exception of such species, however, as would not be likely to meet with the food they are accustomed to live upon, or the same degree of warmth as that to which they have been habituated, as our Parrakeets, the White-headed Pigeon, Zenaida Dove, Booby Gannet, several Terns, Gallinules, Herons, and others, which are by no means deficient in the power of flight, were nothing else required.

Another thought has frequently recurred to me while making observations on the habits of our birds: the nests of all those which advance least to the northward are less bulky than those of the same species found in higher latitudes. This difference I have not considered altogether as depending upon the state of the temperature, but upon the longer time afforded these birds for rearing their young, the old and strong individuals arriving at an early period of the season, so that they have abundance of time to rear their broods before a decided change of temperature takes place. Again, it has become a matter of great doubt with me, whether the necessity of migration has not, in some parts of our countries, been increased in many species by the great increase of the individuals of a species that have settled there, and which have so encroached upon the original occupants as to force them to seek other retreats. In times long gone by, the country was in a manner their own, and being free of annoyance, they probably bred in every portion of the land that proved favourable in regard to food. On the other hand, I am fully aware that many species, now unknown in certain districts, have formerly been abundant there, but have been induced to remove to other sections of the country, enticed thither by the accumulation of food produced by the increase of civilized men. This I would look upon as a proof that migration is not caused solely by an organic or instinctive impulse which induces birds to remove at a particular period to a distant part, to spend a season there for the purpose of reproducing only; but also for the reasons stated above.

Dr. T. M. BREWER has favoured me with the following remarks:--"Your account of the Robin hardly leaves me any thing to add, except the fact that Mr. CABOT found the nest of this bird on the ground (a bare rock) near Newport, Rhode Island. Such a situation is certainly unusual, if not altogether unprecedented. It appears to me that the opinion commonly entertained, that the Robin passes the winter in Massachusetts, is not strictly correct. Sure it is that Robins are to be found here pretty much at all seasons, but I have no idea that the same individuals remain any length of time. They are rather successions of flocks slowly moving towards warmer regions, and have about all passed through the State by the first week of February; from which time until March none are to be found there, when those that visit the extreme northern parts again commence their migrations. In the gardens in the vicinity of Boston, the Robins have become a great nuisance, from the boldness with which they appropriate to their own use the largest, earliest, and best cherries, strawberries, currants, buffalo-berries, raspberries, and other fruit. The Robin generally has three broods in a season, in this State, and in the third nest it is not unusual to find the eggs last laid to be only about a third of the size of the others. Albinoes of this species have sometimes been seen."

The interior of the mouth has the same general structure as that of the Mocking-bird; its width 4 twelfths. The tongue is 8 twelfths long, narrow, tapering, thin, horny, with the margins slightly lacerated, and the tip slit. The posterior aperture of the nares is oblongo-linear, 7 twelfths long. The oesophagus is three inches long, funnel-shaped at the commencement, afterwards of the nearly uniform width of 3 1/2 twelfths, until it enters the thorax, when it contracts; the proventriculus bulbiform, 5 twelfths in breadth. The stomach is of moderate size, broadly elliptical, 9 twelfths in length, 7 1/2 twelfths in breadth; the epithelium light red, longitudinally rugous; the muscles of moderate thickness. The intestine is of moderate length and great width, the former being 13 inches, the latter 4 twelfths. It passes downwards in front, at the distance of 1 1/2 inches, bends forward, inclosing the pancreas, opposite the right lobe of the liver receives the biliary ducts, then passes backwards to the right side until it reaches the hind part of the abdomen, forms two short convolutions, afterwards a larger one, and over the stomach terminates in the rectum. The coeca are 3 twelfths long, 1 twelfth in width; their distance from the extremity 1 inch. The cloaca is an oblong sac, of which the width is 1/2 an inch.

The trachea is 2 inches 2 twelfths long, a little flattened, firm, the rings about 78, with 2 terminal half rings. The bronchi are short, of about 12 half rings. The muscles are as described in the Mocking-bird.

ROBIN, Turdus migratorius, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. i. p. 35.

TURDUS MIGRATORIUS, Bonap. Syn., p. 75.

MERULA MIGRATORIA, Red-breasted Thrush, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer.,vol. ii. p. 176.

AMERICAN ROBIN or MIGRATORY THRUSH, Turdus migratorius, Nutt. Man., vol. i.p.338.

AMERICAN ROBIN or MIGRATORY THRUSH, Turdus migratorius, Aud. Orn. Biog.,vol. ii. p. 190; vol. v. p. 442.

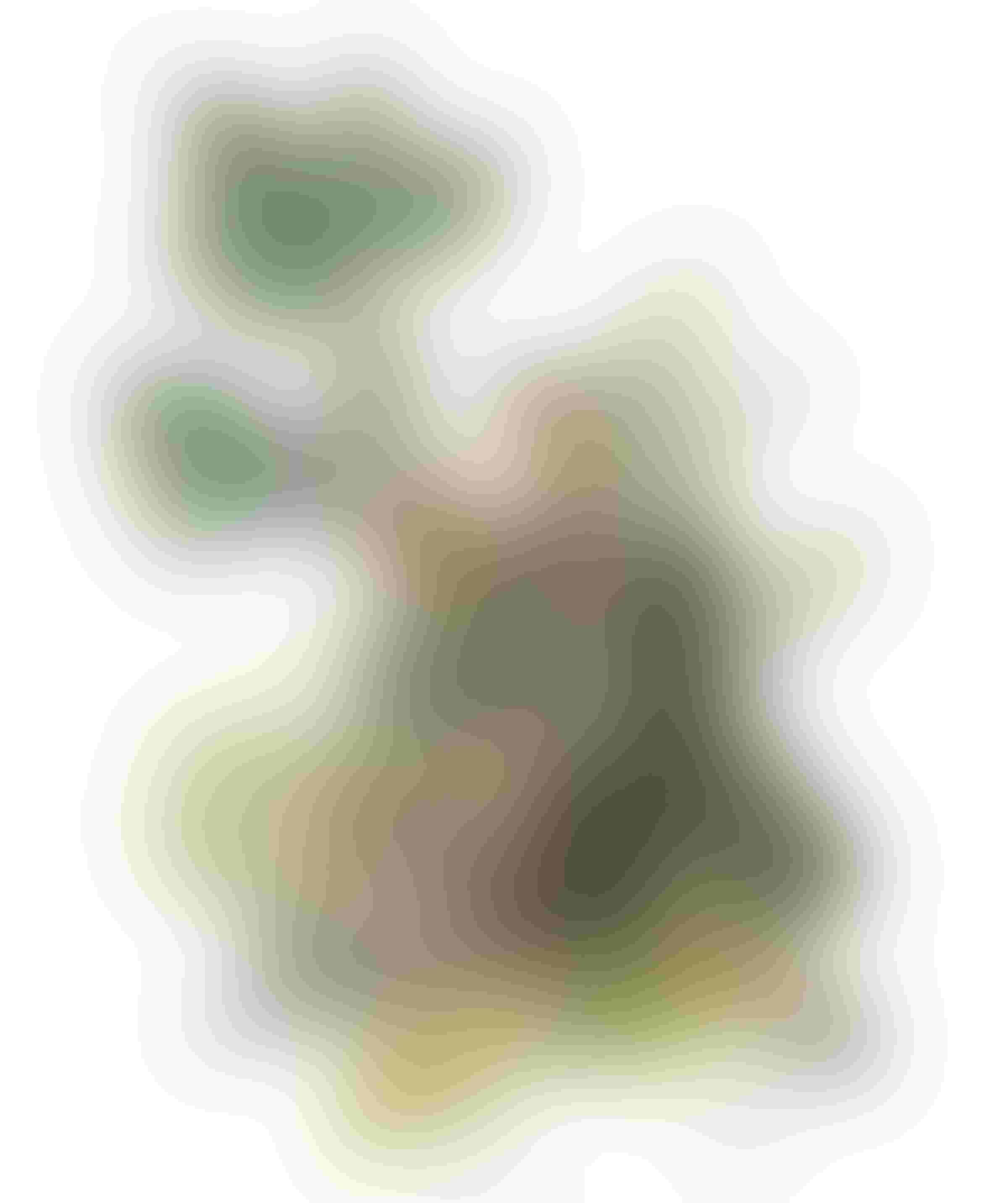

Male with the bill yellow, the upper part and sides of the head black; upper parts dark grey, with an olivaceous tinge; quills blackish-brown, margined with light grey; tail brownish-black, the outer two feathers tipped with white; three white spots about the eye, throat white, densely streaked with black; lower part of fore neck, breast, sides, axillars, and lower wing-coverts reddish-orange; abdomen white; lower tail-coverts dusky, tipped with white. Female with the tints paler. Young with the fore neck, breast, and sides pale reddish, spotted with dusky, the upper parts darker than in the adult. Bill at first dusky, ultimately pure yellow.

Male, 10, 14. Female, 9, 13.

For more on this species, see its entry in the Birds of North America Field Guide.