Andrew Wunderley crouches in the sand to pick up a milky white sphere. He pinches the lentil-size orb between his thumb and forefinger. It nearly pops out of his grip. The little pellet is made of brand-new plastic and has all the wondrous qualities of the material—light, smooth, and virtually forever-lasting. Many more are scattered in the high-tide line of the wide, windswept beach, the pride of Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a barrier island at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. He drops the pellet into a glass jar and picks up another, then another. Just offshore, container ships cut through the January fog on their way to Charleston’s industrial port.

Before plastic is formed into forks or garbage bags or iPhone cases, it is born into the world as these orbs. The plastics industry calls them pre-production pellets, or sometimes just resins. Everyone else—for reasons no one I asked seemed to know—calls them “nurdles.” Just a few months before we met on that January day, Wunderley had never heard of them. And then he received a fateful call.

Wunderley directs Charleston Waterkeeper, a group dedicated to protecting the region’s waterways. A dog walker rambling the beach contacted him after noticing a strange pearling in the sand—hundreds of white spheres pushing up with the surf. “It was almost like sleet,” Wunderley recalls.

Soon after, the state’s environmental agency and the South Carolina Ports Authority came to inspect. After they looked, they went straight to the warehouse of a shipping company called Frontier Logistics. They found pellets sprinkled on the floor, littering the truck loading zone, and pooled in crevices along the train rails. According to the state’s inspection report, these “appeared to resemble” the pellets on the beach. Frontier denied responsibility, but nonetheless paid a cleanup crew to pick up the Sullivan’s Island nurdles by hand.

For Wunderley, that was only the beginning of the story. Once he knew to look, the pellets were seemingly everywhere. His focus soon shifted from sampling for sewer contamination and patrolling creeks to shuffling in mud and sand on hand and knee in search of tiny debris, documenting what had rapidly become a serious problem.

For the past few years Charleston has been transforming into a major plastics export hub. The city is a middle step in the material’s supply chain: Companies receive train cars of nurdles from states like Texas that they then load onto container ships and send overseas. Frontier opened in 2017, and a handful of other companies have either recently begun operating or are planning facilities near the port. Evidence of this expansion has been turning up all along the coast.

Every time Wunderley goes back to this beach, high tides have washed fresh nurdles ashore. Sarah Church, a lifelong resident of the nearby community, has noticed them, too. “I have not found a spot on the beach that I haven’t been able to find them,” she says. Her father, who once clammed the nearby Breach Inlet, would be distressed when he found trash in the marsh. Now, for her, spotting pellets has become a persistent, anxious new orientation to a landscape that had been a comfort since childhood. “I can’t help it—I’m like, ‘There’s one, there’s one, there’s one.’ I walk the dog and I come back with a pocketful of nurdles.”

I later join Wunderley at another sampling site along the port near the tidal mouth of the Cooper River. As fishers cast lines from a pier, Wunderley puts on rubber waders and enters the salt marsh beneath, where the mud is riddled with fiddler crab holes. He immediately spots nurdles tucked in dead spartina grass. There are more here than on the beach that morning because tides flush them out less often. To a tiny nurdle, a blade of fallen grass is a dam.

Again, Wunderley gathers as many as he can find in 10 minutes. The scene is thoroughly Sisyphean. There will always be more. But Wunderley isn’t trying to clean the nurdles up. He is trying to prove they exist—that the problem hasn’t been solved. The spills, he believes, are ongoing. “Frontier’s attitude from the very beginning was, ‘You can’t prove they’re ours,’ ” Wunderley says. “And I’ve never been one to say no to a good challenge.”

The challenge is hardly confined to South Carolina; nurdles are turning up in waterways and on beaches all over the world. What’s more, the tiny pellets are just one symptom of a growing trend: larger volumes of cheap plastic being manufactured faster than ever.

Since its invention more than a century ago, plastic has proven an endlessly adaptable building block of modern life. Its utility is only gaining. More than half of all plastic was produced in the past 15 years. Only about 9 percent made has ever been recycled. That means the vast majority of all plastic created is still here, and it’s accumulating—piling up in landfills and on riverbeds and coasts, and flaking into ever smaller particles that show up in our food supply and the falling snow.

The next 15 years are likely to deliver more plastic than the last. The United States, in particular, is investing billions into ramping up production. As of February, some 343 new plastic production plants and expansions were permitted or planned here in the near future, according to the American Chemistry Council, the plastic industry’s biggest trade group.

The driving force behind the soaring volume of plastics can be attributed to one important factor, a surplus of its raw material—fossil fuels. And in the United States one fossil fuel has become phenomenally abundant and absurdly cheap: Plastic, it turns out, is a great way to profit from the nation’s glut of natural gas.

Until about two decades ago, almost all plastic was made from crude oil, a technique that still dominates in the rest of the world (in China, plastic is increasingly made with coal). Then two developments converged. Researchers pioneered a method to “crack” ethane, previously an unusable waste product of natural gas extraction, enabling the molecules to be rearranged into ethylene, the main component of plastic. And vast deposits of natural gas suddenly became available and cost-efficient, thanks to the combined success of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling.

“What led the massive boom in the construction of new plastics facilities in the U.S. was not the emergence of massive public demand for plastics, but the fact that natural gas feedstocks became incredibly cheap,” says Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law, a nonprofit human rights and environmental law firm that regularly publishes analyses of the plastics industry. “The fracking boom triggered the renaissance of the plastics industry in the U.S.”

This renaissance has driven the cost down, making virgin plastic cheaper, even, than recycled plastic for the first time last year. Based on these economics alone, a manufacturer would be foolish to use anything else.

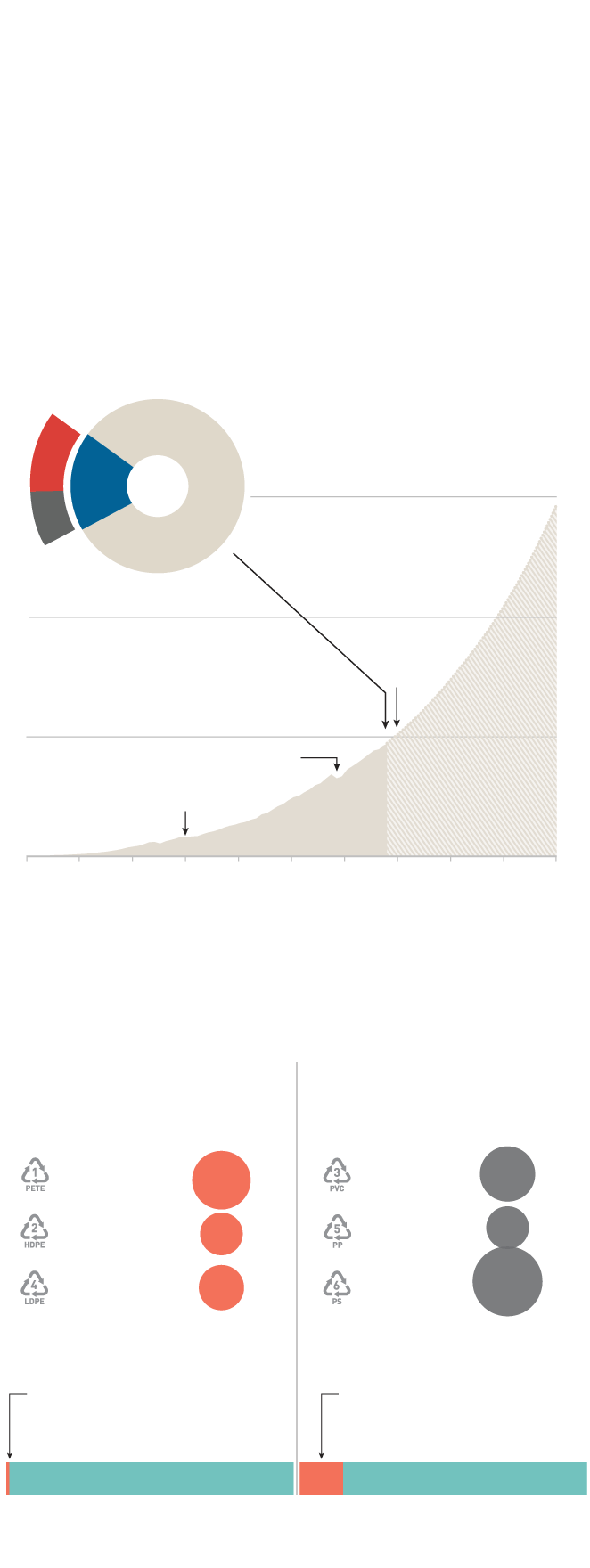

Plastic Pileup

The world produced the weight equivalent of 25,000 Empire State Buildings in plastic from 1950 to 2015. If current trends continue, global annual production may roughly triple by 2050.

Global Plastics, Annually

In 2018 North American made about 20 percent of the world’s plastic, just over half of which was polyethylene.

3,000 billion pounds

2,000

This year’s economic crisis

could cause another dip

1,000

Recession of 2008

Recycling begins

0

1950

1980

2020

2050

Global Emissions

Greenhouse gases increase with production. As clean energy displaces fossil fuels, plastic’s share of total emissions will grow.

Polyethylenes

(from natural gas)

Others

(mostly from oil)

Emissions per

pound of plastic

Emissions per

pound of plastic

Water

bottles

Plastic wrap

2.2

1.5

3.1

2.4

1.5

1.6

Frozen-

food trays

Detergent

bottles

Bags

Coffee cups

Pounds CO2e

Pounds CO2e

Today, emissions from

plastic production is one

percent of the world’s total.

By 2050, that figure may

reach 15 percent, or about

5 trillion pounds annually.

SOURCES: GEYER ET AL., SCIENCE ADVANCES, 2017 (PLASTIC PRODUCTION); WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY, 2016 (PRODUCTION PREDICTIONS); POSEN ET AL., ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LETTERS, 2017 (EMISSIONS); U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (TOTAL U.S. EMISSIONS).

Plastic Pileup

The world produced the weight equivalent of 25,000 Empire State Buildings in plastic from 1950 to 2015. If current trends continue, global annual production may roughly triple by 2050.

Global Plastics, Annually

3,000 billion pounds

This year’s economic crisis could cause another dip.

In 2018 North American made about 20 percent of the world’s plastic, just over half of which was polyethylene.

2,000

Total

production

1,000

Recession of 2008

Recycling begins

0

1950

1980

2020

2050

Global Emissions

Greenhouse gases increase with production. As clean energy displaces fossil fuels, plastic’s share of total emissions will grow.

Polyethylenes

(from natural gas)

Others

(mostly from oil)

Emissions per

pound of plastic

Emissions per

pound of plastic

Water bottles

Plastic wrap

2.2

1.5

3.1

2.4

1.5

1.6

Detergent bottles

Frozen-food trays

Bags

Coffee cups

Pounds CO2e

Pounds CO2e

By 2050, that figure may

reach 15 percent, or about

5 trillion pounds annually.

Today, emissions from

plastic production is one

percent of the world’s total.

SOURCES: GEYER ET AL., SCIENCE ADVANCES, 2017 (PLASTIC PRODUCTION); WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM, THE NEW PLASTICS ECONOMY, 2016 (PRODUCTION PREDICTIONS); POSEN ET AL., ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LETTERS, 2017 (EMISSIONS); U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY (TOTAL U.S. EMISSIONS).

So far, plastics manufacturing has proliferated along the Gulf Coast, where much of the nation’s gas is produced. In Texas last September, for example, construction began on one of the world’s largest ethane crackers, built by Exxon and Saudi Arabia’s state petrochemical company. In Louisiana in early 2019, South African company Sasol Ltd. opened the first of its seven new virgin plastic plants planned for the state. Recently the Ohio River Valley, where gas drilling has also grown dramatically, has become another hotspot. The sprawling 386-acre campus of a Shell cracker in construction near Pittsburgh is set to produce 1.8 million tons of plastic each year.

Each of these plants produces plastic pellets and powders—another raw form of the material—to be sold domestically or shipped overseas. Production is spiking so dramatically that the port of Houston is running out of room for ships to export it all. More and more pellet trains now crisscross the country, headed for the nation’s large deep-water ports, including Long Beach, California; Savannah, Georgia; and, increasingly, Charleston. From there, they are shipped mostly to Europe or Asia, destined to be used to make products.

At least some of the pellets at Frontier’s facility would likely become plastic packaging or film, if one connects the dots between the inspection report and a technical data sheet for one type of pellet it received: a brand name called Marlex D139, made by Chevron Phillips Chemical. The state has used tax credits to court companies like Frontier to relocate to Charleston, more than tripling its plastic exports since 2017. Last October another company, A&R Logistics, announced a $60 million plastics logistics facility near Charleston, and as of January, Frontier planned to increase its volume, according to the company.

All of these companies along the supply chain are betting on continued natural gas supply, and an ongoing demand for plastics. “The value and benefit of the plastic industry to health care, safety, food production and preservation, and many other sectors of our society we assume will continue to grow,” said a Frontier Logistics spokesperson.

In recent months, the coronavirus pandemic has sent the oil-and-gas industry into an uncertain free fall, and construction on some planned plastics facilities has been stalled, but long-term outlooks prior to the crisis indicated this would be a profitable bet. As a whole, the fossil fuel industry has aimed to increase the rate of plastic production by another third by 2025. By 2050, they intend to more than triple it. By then, petrochemical production—of which the majority is plastic—is slated to account for 50 percent of all growth in demand for fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency.

With that growth, greenhouse gas emissions from plastic production alone could account for an estimated 15 percent of global emissions by mid-century, triple its proportion today. In other words, at a time when scientists say the world must dramatically reduce emissions from all sectors, plastic is moving the needle in the opposite direction.

In St. James Parish, Louisiana, about an hour northwest of New Orleans, one of the world’s largest plastics companies, Formosa Plastics Corp., intends to build a 2,400-acre, $9.4 billion complex, subsidized by $1.5 billion in tax breaks. It would be among the biggest in the nation. The state issued permits in January. For Sharon Lavigne, a retired teacher who grew up in a rural town in the parish, the facility is the final straw. It’s set to be built two miles from her house. “We already have 12 petrochemical plants and refineries within a 10-mile radius,” she says. “If this plant comes we will not be able to breathe the air.”

For many communities nearest to the supply chain that makes plastic possible, environmental consequences of the material are not abstract. Living near a fracking well pad comes with air and drinking-water pollution that creates a host of health concerns. The estimated 3 million miles of natural gas pipelines winding through the United States are prone to leaks and accidents and emit air pollutants. In the Manchester neighborhood of Houston, 90 percent of residents live within one mile of a petrochemical facility, many of which are involved in a stage of plastic production. Cancer risk was found to be 24 to 30 percent higher than in the city’s wealthier neighborhoods, when measured in 2015.

The problems are also acute in Lavigne’s part of Louisiana, known nationally as “cancer alley” because of emissions from the many chemical plants that crowd the region. The air in the parish smells acrid, sometimes like chlorine, other times like rotten eggs, she says. Visitors who spend a few hours may leave with a headache. “We’re already sick. We have so many people that are dying,” she says, recounting neighbors with cancer, asthma, and diabetes. Nearby St. John the Baptist Parish has some of the country’s highest cancer risk. In one town, it’s 50 times the U.S. average.

After the plastic is manufactured, it then presents a new issue: spillage along the supply chain. In a 2019 case, a federal judge ruled that Formosa Plastics Corp. pay $50 million for violating state and federal water pollution laws at another of its ethane cracker facilities, in Lavaca Bay, Texas. The judgment noted more than 1,100 days of violations, based on years of data collected by volunteers who kayaked relentlessly around a nearby creek, counting nurdles. They found Formosa released millions of pellets into the bay, a cove that washes into the Gulf of Mexico.

To get nurdles onto trucks and train cars, workers use pneumatic hoses. But these are not leak-proof, says Miriam Gordon, director of plastic policy advocacy group Upstream; where a hose connects to a valve, there is spill potential. Huge sacks used to pack pellets for shipment can split open easily, too. Once released, pellets are hard to recover, and there’s little incentive to try—the material is so cheap, and spilled nurdles are considered tainted anyway. The industry does maintain a voluntary program called Operation Clean Sweep, whose members commit to best practices for preventing spills, but no oversight mechanism exists.

In California, which is home to hundreds of small companies that transport, repackage, or make products out of nurdles, Gordon has documented pellets tumbling out of water-discharge pipes. Most facilities sit on rivers and tributaries with storm-drain outlets that connect to the waterways. Plastic powders—which can prove an even worse problem—are favored by companies that specialize in “rotational molding,” a technique that creates seamless plastic objects like kayaks. It can result in copious debris that is almost impossible to clean up. “I’ve walked in yards that use the powder and it fills up the cuffs of my pants,” says Charles Moore, a U.S. merchant marine captain and founder of the Algalita Marine Research & Education Foundation. “It’s like walking in sand dunes on the beach. It’s a foot thick.”

Little research exists to quantify how many nurdles, globally, leak into the environment, but a growing movement is filling that gap. When Wunderley and his colleague, scientist Cheryl Carmack, wanted to document the nurdles they were seeing, they talked to Jace Tunnell, a University of Texas researcher and director of a national estuarine research reserve. In 2018, when nurdles suddenly began turning up by the millions on a 30-mile stretch of coast in Corpus Christi, state and U.S. Coast Guard authorities told Tunnell there wasn’t much they could do to find the source or clean them up. “I said, ‘At least count them?’ They said no, they don’t have the manpower for that,” he says.

So Tunnell and a group of volunteers set out to do it themselves, starting Nurdle Patrol, a crowdsourced database. Crucially, they encourage a standard methodology for conducting counts, so researchers can compare and analyze the data. In the project’s first year, volunteers across the country logged 255,531 nurdles. Some of that data provided evidence in the Formosa case in Lavaca Bay. In Europe, groups in Scotland and Belgium—two of the continent’s biggest petrochemical hubs—also count nurdles that show up on beaches in high numbers. In both nations, the plastic had been made from fracked U.S. natural gas, which sailed across the Atlantic in specialized ships.

As with plastic in general, the short- and long-term health effects of this pellet pollution for wildlife and humans is poorly understood. One concern is that shorebirds like Red Knots could mistake nurdles for food. “They resemble fish eggs or horseshoe crab eggs,” says Jen Tyrrell of Charleston Audubon. Nurdles have been found in the bellies of Atlantic Puffins in Scotland, Wedge-tailed Shearwaters on a remote Australian island, and other species.

Once ingested, nurdles can be conduits for contaminants, says Zhanfei Liu, an organic geochemist at the University of Texas Marine Science Institute. He is leading some of the first research into the ways nurdles can pick up and carry toxic chemicals that cling to their surfaces, including carcinogens like polychlorinated biphenyls. The longer nurdles stay in the environment, he and his students have found, the more pocked and cracked they become, providing more surface area for contaminants.

Liu, who usually studies oil spills, had already been troubled by how long plastic pellets endure. Now he’s even warier. “They’re so light, they’ll always stay on the shoreline,” he says. “There are a lot of ecological impacts that we don’t know.”

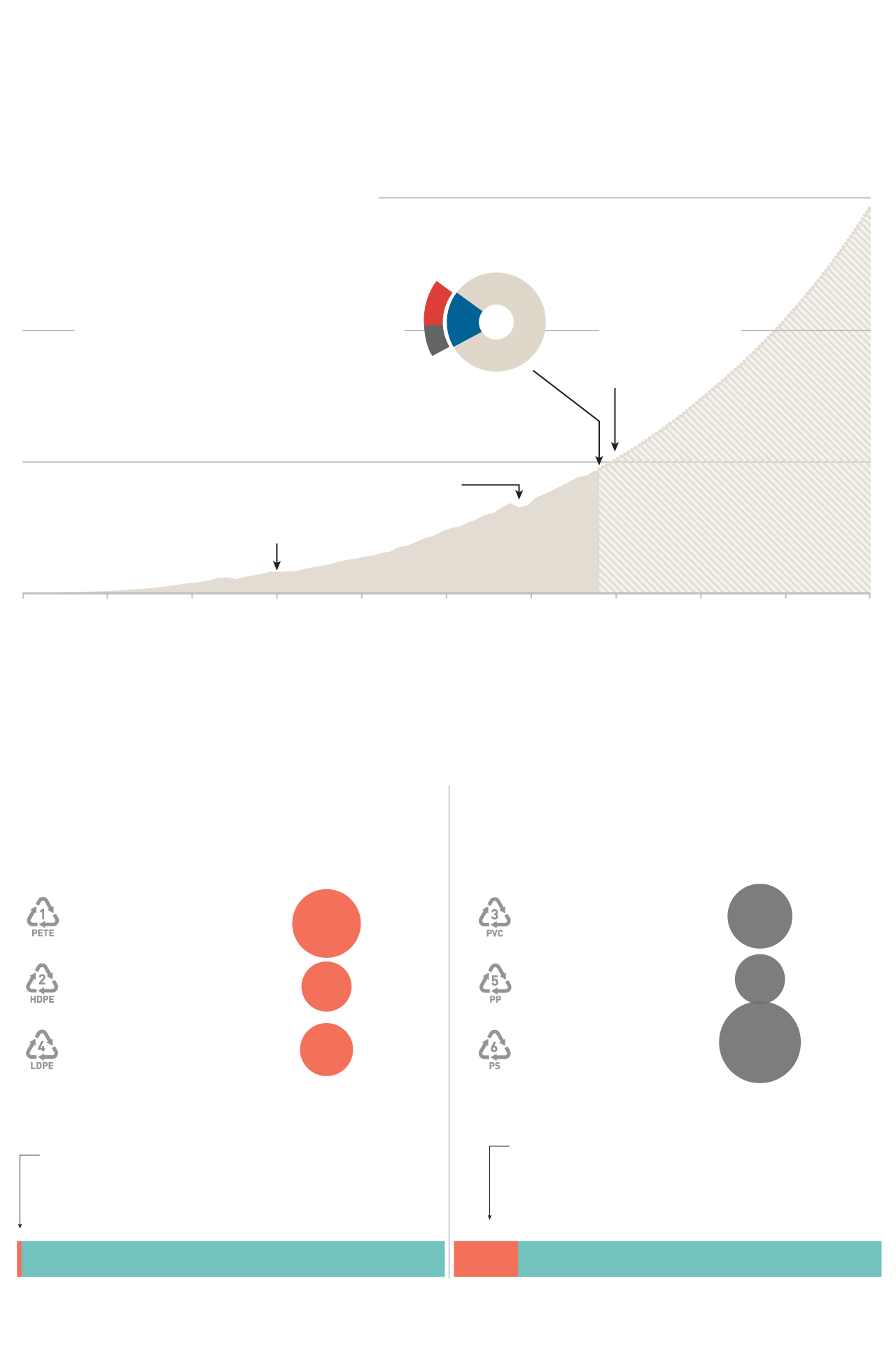

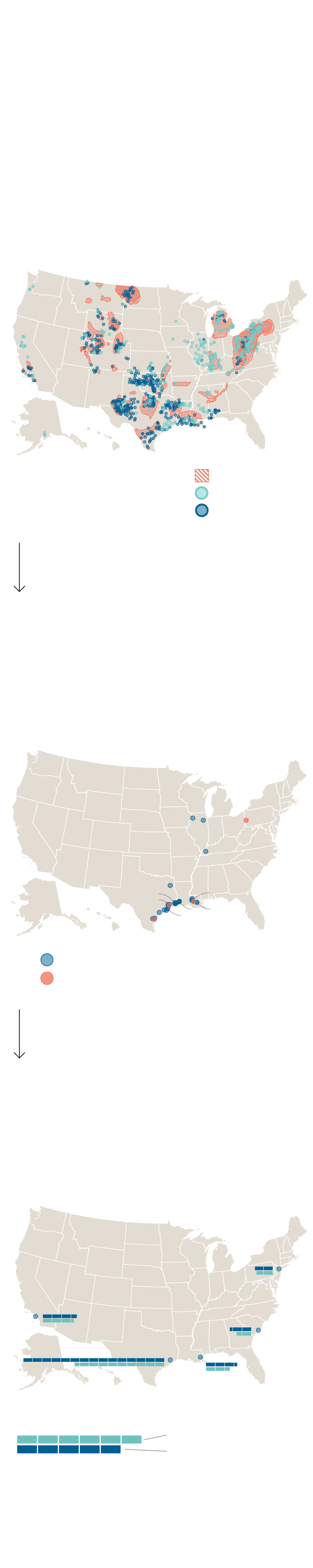

Boomtown USA

Even before plastic becomes a useful product, there’s a less visible chain of impacts linked to rising production.

Drilling Down

Advances in hydraulic fracturing have enabled industry to tap previously unutilized natural gas deposits in shale formations, leading to greater U.S. supplies and lower prices.

Pink areas show where U.S. shale holds natural gas reserves. The dots indicate facilities.

Shale deposits

Natural gas storage

Processing plants

Ethane, a product of natural gas extraction, is separated and transported, usually by pipeline, to petrochemical facilities.

Cracking Up

To create plastic, ethane is split—cracked—to form ethylene, the building block for polyethylene. Each dot marks one ethane cracker (in-progress facilities aren’t an exhaustive list).

7

5

5

2

4

2

Gulf Coast: 27 crackers

Operational

In-progress

Plastic pellets and powders are typically shipped by train or truck to domestic manufacturing plants or to major U.S. ports.

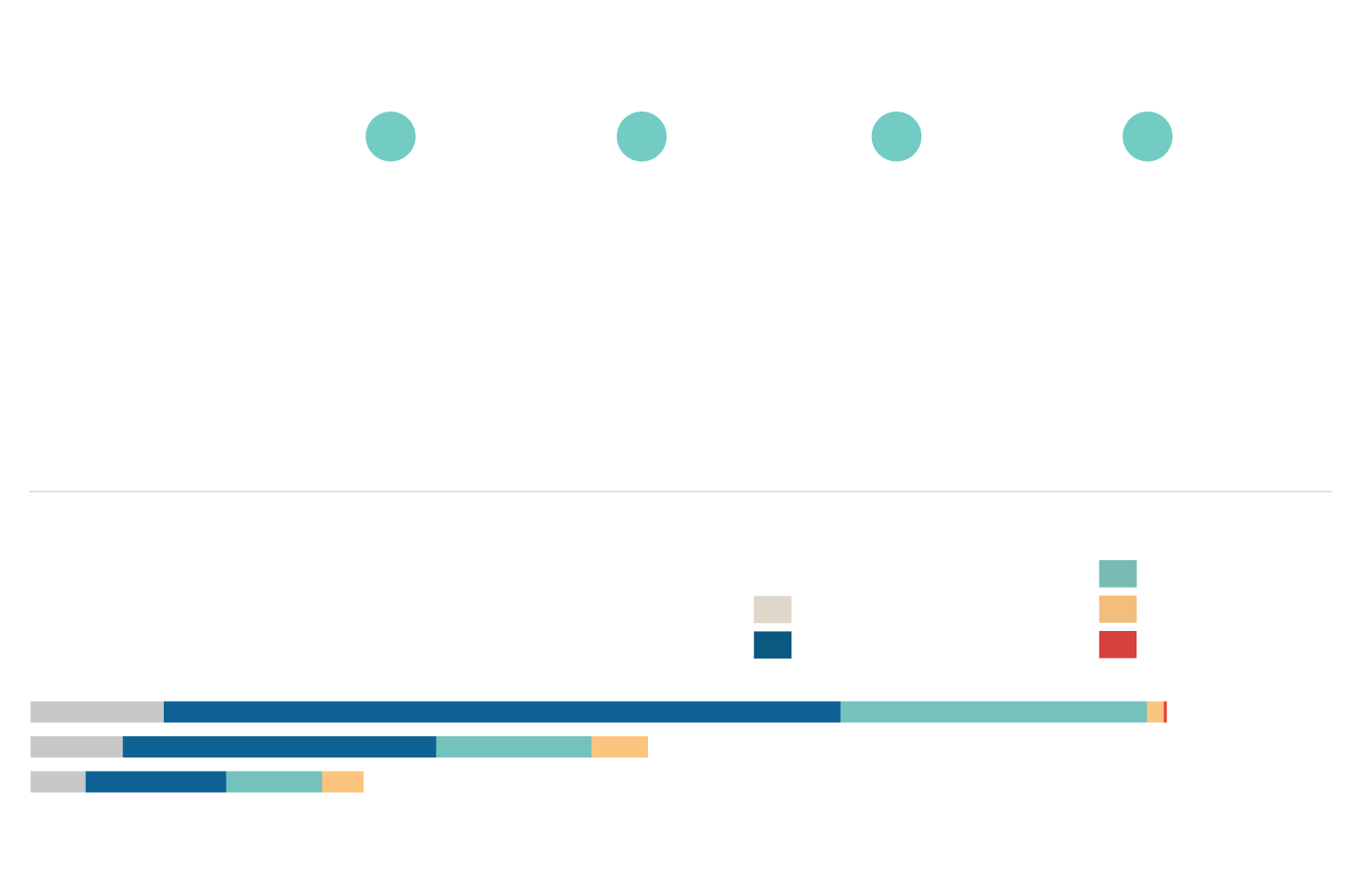

Shipping Out

Up to 40 percent of North American plastic is exported, and the volume is rising. In the first half of 2019 Houston shipped enough plastic to fill 15 of these vessels or more than 200,000 20-foot-long shipping containers.

New York and New Jersey

9% growth

Los Angeles and Long Beach

Charleston

10% growth

48% growth

Houston

New Orleans

57% growth

31% growth

Exports by Port

First half of 2019

First half of 2018

Blocks equal 13,000 TEUs of resin—the capacity of some of the largest ships that fit through the Panama Canal.

SOURCES: U.S. ENERGY INFORMATION ADMINISTRATION (NATURAL GAS DATA, CRACKERS), PETROCHEMICAL UPDATE (CRACKERS), IHS MARKIT (CRACKERS, PLASTIC EXPORTS BY PORT).

Boomtown USA

Even before plastic becomes a useful product, there’s a less visible chain of impacts linked to rising production.

Drilling Down

Advances in hydraulic fracturing have enabled industry to tap previously unutilized natural gas deposits in shale formations, leading to greater U.S. supplies and lower prices.

Pink areas show where U.S. shale holds natural gas reserves. The dots indicate facilities.

Shale deposits

Natural gas storage

Processing plants

Ethane, a product of natural gas extraction, is separated and transported, usually by pipeline, to petrochemical facilities.

Cracking Up

To create plastic, ethane is split—cracked—to form ethylene, the building block for polyethylene. Each dot marks one ethane cracker (in-progress facilities aren’t an exhaustive list).

Operational

In-progress

5

7

5

2

4

2

Gulf Coast: 27 crackers

Plastic pellets and powders are typically shipped by train or truck to domestic manufacturing plants or to major U.S. ports.

Shipping Out

Up to 40 percent of North American plastic is exported, and the volume is rising. In the first half of 2019 Houston shipped enough plastic to fill 15 of these vessels or more than 200,000 20-foot-long shipping containers.

Blocks equal 13,000 TEUs of resin—the capacity of some of the largest ships that fit through the Panama Canal.

Exports by Port

First half of 2019

First half of 2018

New York and New Jersey

9% growth

Los Angeles and Long Beach

Charleston

10% growth

48% growth

Houston

New Orleans

57% growth

31% growth

SOURCES: U.S. ENERGY INFORMATION ADMINISTRATION (NATURAL GAS DATA, CRACKERS), PETROCHEMICAL UPDATE (CRACKERS), IHS MARKIT (CRACKERS, PLASTIC EXPORTS BY PORT).

At Nana’s Seafood & Soul, a beloved spot in North Charleston, customers line up while Kenyatta McNiel takes lunch orders. He goes into the kitchen and emerges with fried shrimp and pineapple sweet teas. The straws are paper, and the containers are compostable. In January a single-use plastic ban took effect for Charleston, so Nana’s had recently phased out plastic takeout containers.

In a slow moment, I ask him how the transition went for Nana’s and he laughs. It’s been tough. The new fiber clamshells are more expensive than the plastic ones. He’s looking for cheaper options. But for now, he’s losing money on the soup; the container is costlier than his profit margin. “But I guess it’s good for the environment,” he says sincerely, before taking a phone order.

Along a coast prized for its beaches and seafood, Charleston’s single-use-plastic ban found enthusiastic support. Despite efforts, however, no similar ban has passed for the state. The industry has lobbied heavily against this and, in fact, backed several proposed “preemption bills” that would invalidate local bans if passed. This tug-of-war is echoed elsewhere: While only eight states ban single-use plastic bags, nearly twice as many have outlawed the act of cities banning them. More recently, industry groups have also used the coronavirus pandemic to lobby against bans, positioning plastic as a more hygienic choice, despite evidence that the virus could survive on the material for up to three days.

The difficult truth is that, no matter what Charleston residents and small businesses do to shun plastic, it ends up in their harbor. This is the conundrum of the global plastic crisis in a nutshell: Large-scale economic forces, guided by subsidies and industry lobbying, have made plastic a cheap, unavoidable choice.

“We are constantly trying to make these beaches cleaner...we use biodegradable poop bags for the dogs. We’re really trying,” says Church, who sits on the Sullivan’s Island town council. “It’s just really heartbreaking to see our beaches littered like that and feel so powerless over it.”

Very recently there have been hints, however, that the U.S. plastic boom could become a bubble. Even before this year’s economic crisis, signs were emerging that the growth in demand the industry predicted might not materialize as hoped, says Muffett. The U.S. market was flooded with cheap plastic and not enough places to sell or export it. Several planned projects were put on hold. Natural gas prices had also dropped so low that some U.S. gas producers burned off supply onsite because it was no longer worth the cost to process and transport. And then there have been bans, like Charleston’s, but much larger. China, for example, announced a ban last year. In Africa, 34 countries have imposed rules restricting some single-use plastics. “These were precisely the markets the industry predicted would be the source of their long-term growth,” Muffett says. “The industry’s assumption that they would be able to sell ever greater volumes of plastic is proving ill-founded.”

The pandemic fallout has created more uncertainty. Still, if the petrochemical industry secures a bailout and succeeds in stifling plastic bans around the world, the nation’s plastic expansion is likely to move forward as planned. Its trajectory is in flux.

Resistance to pollution from plastic production is also emerging, from the grassroots nurdle counts and protests against new facilities to the proposed federal Break Free from Plastics Act, which would bar discharges of resins from production sites, among other provisions. Late last year some 350 groups filed a petition calling on EPA to adopt stricter air-pollution standards for such plants. In Louisiana Lavigne has founded an environmental justice group called Rise St. James. She and other residents have repeatedly asked the parish and state to rescind Formosa’s air-pollution and land-use permits, thus far to no avail. A construction crew broke ground on the site in late March, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

In South Carolina, environmentalists have also banded together to address the plastic pollution problem. In March, with the Southern Environmental Law Center and the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League, Charleston Waterkeeper filed a lawsuit against Frontier. Their goal: to use Wunderley’s evidence to show that the spill last July was not a one-off event.

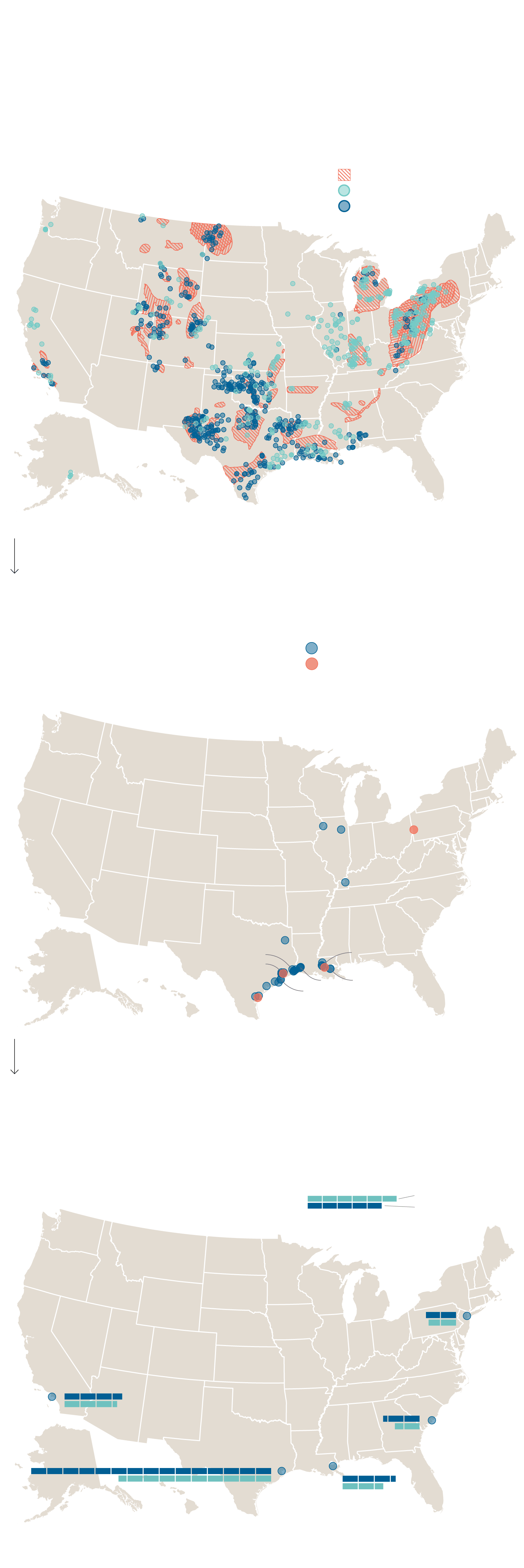

How To Do a Nurdle Hunt

Nurdle Patrol, in the United States, and the

Great Nurdle Hunt, in the United Kingdom, are collecting data on plastic pellet pollution. Participate by visiting a local beach or shore.

1

2

Go to the water line and look for a nurdle. If you don’t see one, check the recent high tide line or the foot of sand dunes. You might have to get on your knees to spot them.

Start a timer when you find one and collect as many as you can in 10 minutes. If you don’t find any, “zero” is also useful data to share.

3

4

Count your nurdles, and, remember, they don’t belong there—take them with you for disposal. Record the number of people who were sampling.

Submit the data to nurdlepatrol.org. Locate your sampling site on the map; you can also opt to submit a photo.

Total Hunts by Geography

The two nurdle initiatives have together tallied nearly 5,000 counts. Some turn up no pellets at all; others have reported thousands. Counts are as of May 2020.

U.S. 2,633

U.K. 1,430

Everywhere else 771

Nurdles found in 10 min.

50-500

500-5,000

5,000-30,000

None

0-50

How To Do a Nurdle Hunt

Nurdle Patrol, in the United States, and the Great Nurdle Hunt, in the United Kingdom, are collecting data on plastic pellet pollution. Participate by visiting a local beach or shore.

1

2

3

4

Count your nurdles, and, remember, they don’t belong there—take them with you for disposal. Record the number of people who were sampling.

Submit the data to nurdlepatrol.org. Locate your sampling site on the map; you can also opt to submit a photo.

Go to the water line and look for a nurdle. If you don’t see one, check the recent high tide line or the foot of sand dunes. You might have to get on your knees to spot them.

Start a timer when you find one and collect as many as you can in 10 minutes. If you don’t find any, “zero” is also useful data to share.

Total Hunts by Geography

Nurdles found in 10 min.

50-500

500-5,000

5,000-30,000

The two nurdle initiatives have together tallied nearly 5,000 counts. Some turn up no pellets at all; others have reported thousands. Counts are as of May 2020.

None

0-50

U.S. 2,633

U.K. 1,430

Everywhere else 771

After Wunderley collects nurdles, Carmack counts them out on a pharmacists’ pill tray. A dental tooth-decay color chart helps her categorize the pellets’ age. They tend to turn yellow and then brown with more time in the ocean—“a lot like teeth,” she says. Hundreds of these jars, organized by nurdle shape and degree of weathering, now fill a corner in the small room that serves as the Waterkeeper headquarters. “Different shapes mean different spills,” she says, opening drawers to show rows of jars. They looked like the haunting wares of a desaturated candy shop.

Even with their best documentation efforts, a lack of clear regulations makes the lawsuit an uphill battle. After the spill last summer, Frontier installed silt fencing and sandbags, instituted cleanup shifts, and put temporary barriers along the pier’s edge, according to the state’s assessment. The South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control dropped the notice of alleged violation without issuing fines.

Part of the reason: Pellets aren’t explicitly covered by state water-discharge laws. “It’s this new regulatory Wild West,” says Emily Cedzo, land, water, and wildlife director at the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League. Many groups that have asked EPA to regulate air pollution from plastics facilities also filed a Clean Water Act petition for the agency to examine water-pollution standards at these plants. Yet, for now, no federal rules exist to address pellets either.

At a public meeting months after the spill, S.C. Ports Authority chief executive Barbara Melvin said that “astronomical high tides and rain” the week of the spill made it an unusual incident. But, she added, plastic was uncharted territory. “This is a new phenomenon on the East Coast,” she told the town council, and they’d learned from the spill event. Recently, South Carolina state senator Sandy Senn, a Republican, introduced a bill to add language about nurdles to the state’s water-discharge laws.

Wunderley and I drive to a final location: the strip of curb along a fence that runs the perimeter of Frontier’s lot. We are several hundred yards away from its warehouse building, which is perched on a pier. He brushes aside some leaf litter along the curb. “Holy shit, here you go,” he says, picking up four or five pellets in a single pinch.

In 10 minutes, he picks up more than 100 nurdles, by far the highest count of the day. This adds to the data they’ll bring to court, if the lawsuit makes it that far. Wunderley and Carmack had been sampling every week for eight months, until coronavirus hit the region in March. But they’d collected enough data anyway. They had consistently found nurdles on either side of Frontier’s pier. There may be other sources as well; they find the pellets at train crossings inland, wedged in the traprock between rails.

Ultimately each nurdle Wunderley collects reflects a global story that’s bigger than any one facility. Without laws to address plastic production and consumption, the story is unlikely to change. “I think it’s a much bigger problem than we understand,” he says. “I’ve got a gut feeling I’m going to be working on this issue for the rest of my career.”

This story originally ran in the Summer 2020 issue. To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.