Plate 156

American Crow

The Crow is an extremely shy bird, having found familiarity with man no way to his advantage. He is also cunning--at least he is so called, because he takes care of himself and his brood. The state of anxiety, I may say of terror, in which he is constantly kept, would be enough to spoil the temper of any creature. Almost every person has an antipathy to him, and scarcely one of his race would be left in the land, did he not employ all his ingenuity, and take advantage of all his experience, in counteracting the evil machinations of his enemies. I think I see him perched on the highest branch of a tree, watching every object around. He observes a man on horseback travelling towards him; he marks his movements in silence. No gun does the rider carry,--no, that is clear; but perhaps he has pistols in the holsters of his saddle!--of that the Crow is not quite sure, as he cannot either see them or "smell powder." He beats the points of his wings, jerks his tail once or twice, bows his head, and merrily sounds the joy which he feels at the moment. Another man he spies walking across the field towards his stand, but he has only a stick. Yonder comes a boy shouldering a musket loaded with large shot for the express purpose of killing Crows! The bird immediately sounds an alarm; he repeats his cries, increasing their vehemence the nearer his enemy advances. All the Crows within half a mile round are seen flying off, each repeating the well known notes of the trusty watchman, who, just as the young gunner is about to take aim, betakes himself to flight. But alas, he chances unwittingly to pass over a sportsman, whose dexterity is greater; the mischievous prowler aims his piece, fires;--down towards the earth, broken-winged, falls the luckless bird in an instant. "It is nothing but a Crow," quoth the sportsman, who proceeds in search of game, and leaves the poor creature to die in the most excruciating agonies.

Wherever within the Union the laws encourage the destruction of this species, it is shot in great numbers for the sake of the premium offered for each Crow's head. You will perhaps be surprised, reader, when I tell you that in one single State, in the course of a season, 40,000 were shot, besides the multitudes of young birds killed in their nests. Must I add to this slaughter other thousands destroyed by the base artifice of laying poisoned grain along the fields to tempt these poor birds? Yes, I will tell you of all this too. The natural feelings of every one who admires the bounty of Nature in providing abundantly for the subsistence of all her creatures, prompt me to do so. Like yourself, I admire all her wonderful works, and respect her wise intentions, even when her laws are far beyond our limited comprehension.

The Crow devours myriads of grubs every day of the year, that might lay waste the farmer's fields; it destroys quadrupeds innumerable, every one of which is an enemy to his poultry and his flocks. Why then should the farmer be so ungrateful, when he sees such services rendered to him by a providential friend, as to persecute that friend even to the death? Unless he plead ignorance, surely he ought to be found guilty at the bar of common sense. Were the soil of the United States, like that of some other countries, nearly exhausted by long continued cultivation, human selfishness in such a matter might be excused, and our people might look on our Crows, as other people look on theirs; but every individual in the land is aware of the superabundance of food that exists among us, and of which a portion may well be spared for the feathered beings, that tend to enhance our pleasures by the sweetness of their song, the innocence of their lives, or their curious habits. Did not every American open his door and his heart to the wearied traveller, and afford him food, comfort and rest, I would at once give up the argument; but when I know by experience the generosity of the people, I cannot but wish that they would reflect a little, and become more indulgent toward our poor, humble, harmless, and even most serviceable bird, the Crow.

The American Crow is common in all parts of the United States. It becomes gregarious immediately after the breeding season, when it forms flocks sometimes containing hundreds, or even thousands. Towards autumn, the individuals bred in the Eastern Districts almost all remove to the Southern States, where they spend the winter in vast numbers.

The voice of our Crow is very different from that of the European species which comes nearest to it in appearance, so much so indeed, that this circumstance, together with others relating to its organization, has induced me to distinguish it, as you see, by a peculiar name, that of Corvus Americanus. I hope you will think me excusable in this, should my ideas prove to be erroneous, when I tell you that the Magpie of Europe is assuredly the very same bird as that met with in the western wilds of the United States, although some ornithologists have maintained the contrary, and that I am not disposed to make differences in name where none exist in nature. I consider our Crow as rather less than the European one, and the form of its tongue does not resemble that of the latter bird; besides the Carrion Crow of that country seldom associates in numbers, but remains in pairs, excepting immediately after it has brought its young abroad, when the family remains undispersed for some weeks.

Wherever our Crow is abundant, the Raven is rarely found, and vice versa. From Kentucky to New Orleans, Ravens are extremely rare, whereas in that course you find one or more Crows at every half mile. On the contrary, far up the Missouri, as well as on the coast of Labrador, few Crows are to be seen, while Ravens are common. I found the former birds equally scarce in Newfoundland.

Omnivorous like the Raven, our Crow feeds on fruits, seeds, and vegetables of almost every kind; it is equally fond of snakes, frogs, lizards, and other small reptiles; it looks upon various species of worms, grubs and insects as dainties; and if hard pressed by hunger, it will alight upon and devour even putrid carrion. It is as fond of the eggs of other birds as is the Cuckoo, and, like the Titmouse, it will, during a paroxysm of anger, break in the skull of a weak or wounded bird. It delights in annoying its twilight enemies the Owls, the Opossum, and the Racoon, and will even follow by day a fox, a wolf, a panther, or in fact any other carnivorous beast, as if anxious that man should destroy them for their mutual benefit. It plunders the fields of their superabundance, and is blamed for so doing, but it is seldom praised when it chases the thieving Hawk from the poultry-yard.

The American Crow selects with uncommon care its breeding place. You may find its nest in the interior of our most dismal swamps, or on the sides of elevated and precipitous rocks, but almost always as much concealed from the eye of man as possible. They breed in almost every portion of the Union, from the Southern Cape of the Floridas to the extremities of Maine, and probably as far westward as the Pacific Ocean. The period of nestling varies from February to the beginning of June, according to the latitude of the place. Its scarcity on the coast of Labrador, furnishes one of the reasons that have induced me to believe it different from the Carrion Crow of Europe; for there I met with several species of birds common to both countries, which seldom enter the United States farther than the vicinity of our most eastern boundaries.

The nest, however, greatly resembles that of the European Crow, as much, in fact, as that of the American Magpie resembles the nest of the European. It is formed externally of dry sticks, interwoven with grasses, and is within thickly plastered with mud or clay, and lined with fibrous roots and feathers. The eggs are from four to six, of a pale greenish colour, spotted and clouded with purplish-grey and brownish-green. In the Southern States they raise two broods in the season, but to the eastward seldom more than one. Both sexes incubate, and their parental care and mutual attachment are not surpassed by those of any other bird. Although the nests of this species often may be found near each other, their proximity is never such as occurs in the case of the Fish-Crow, of which many nests may be seen on the same tree.

When the nest of this species happens to be discovered, the faithful pair raise such a hue and cry that every Crow in the neighbourhood immediately comes to their assistance, passing in circles high over the intruder until he has retired, or following him, if he has robbed it, as far as their regard for the safety of their own will permit them. As soon as the young leave the nest, the family associates with others, and in this manner they remain in flocks till spring. Many Crows' nests may be found within a few acres of the same wood, and in this particular their habits accord more with those of the Rooks of Europe (Corvus frugilegus), which breed and spend their time in communities. The young of our Crow, like that of the latter species, are tolerable food when taken a few days before the period of their leaving the nest.

The flight of the American Crow is swift, protracted, and at times performed at a great elevation. They are now and then seen to sail among the Turkey Buzzards or Carrion Crows, in company with their relatives the Fish-Crows, none of the other birds, however, shewing the least antipathy towards them, although the Vultures manifest dislike whenever a White-headed Eagle comes among them.

In the latter part of autumn and in winter, in the Southern States, this Crow is particularly fond of frequenting burnt grounds. Even while the fire is raging in one part of the fields, the woods, or the prairies, where tall grass abounds, the Crows are seen in great numbers in the other, picking up and devouring the remains of mice and other small quadrupeds, as well as lizards, snakes, and insects, which have been partly destroyed by the flames. At the same season they retire in immense numbers to roost by the margins of ponds, lakes, and rivers, covered with a luxuriant growth of rank weeds or cat-tails. They may be seen proceeding to such places more than an hour before sunset, in long straggling lines, and in silence, and are joined by the Grakles, Starlings, and Reed-birds, while the Fish-Crows retire from the very same parts to the interior of the woods many miles distant from any shores.

No sooner has the horizon brightened at the approach of day, than the Crows sound a reveille, and then with mellowed notes, as it were, engage in a general thanksgiving for the peaceful repose they have enjoyed. After this they emit their usual barking notes, as if consulting each other respecting the course they ought to follow. Then parties in succession fly off to pursue their avocations, and relieve the reeds from the weight that bent them down.

The Crow is extremely courageous in encountering any of its winged enemies. Several individuals may frequently be seen pursuing a Hawk or an Eagle with remarkable vigour, although I never saw or heard of one pouncing on any bird for the purpose of preying on it. They now and then teaze the Vultures, when those foul birds are alighted on trees, with their wings spread out, but they soon desist, for the Vultures pay no attention to them.

The most remarkable feat of the Crow, is the nicety with which it, like the Jay, pierces an egg with its bill, in order to carry it off, and eat it with security. In this manner I have seen it steal, one after another, all the eggs of a wild Turkey's nest. You will perceive, reader, that I endeavour to speak of the Crow with all due impartiality, not wishing by any means to conceal its faults, nor withholding my testimony to its merits, which are such as I can well assure the farmer, that were it not for its race, thousands of corn-stalks would every year fall prostrate, in consequence of being cut over close to the ground by the destructive grubs which are called "cut-worms."

I never saw a pet Crow in the United States, and therefore cannot say with how much accuracy they may imitate the human voice, or, indeed, if they possess the power of imitating it at all, which I very much doubt, as in their natural state they never evince any talents for mimicry. I cannot say if it possess the thieving propensities attributed by authors to the European Crow.

Its gait, while on the ground, is elevated and graceful, its ordinary mode of progression being a sedate walk, although it occasionally hops when under excitement. It not unfrequently alights on the backs of cattle, to pick out the worms lurking in their skin, in the same manner as the Magpie, Fish-Crow, and Cow-bird. Its note or cry may be imitated by the syllables caw, caw, caw, being different from the cry of the European Carrion Crow, and resembling the distant bark of a small dog.

At Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania I saw a pair of Crows perfectly white, in the possession of Mr. LAMPDIN, the owner of the museum there, who assured me that five which were found in the nest were of the same colour.

Although the common American Crow ranges from the Gulf of Mexico to the shores of the Columbia river, where it is abundant, as well as on the Rocky Mountains, it does not, according to Dr. RICHARDSON, proceed farther north than the 55th parallel of latitude, nor approach within five or six hundred miles of Hudson's Bay, appearing in the Fur Countries during the summer only. I found it abundant in the Texas, where it breeds. The eggs measure one inch five-eighths in length, an inch and one-eighth in breadth.

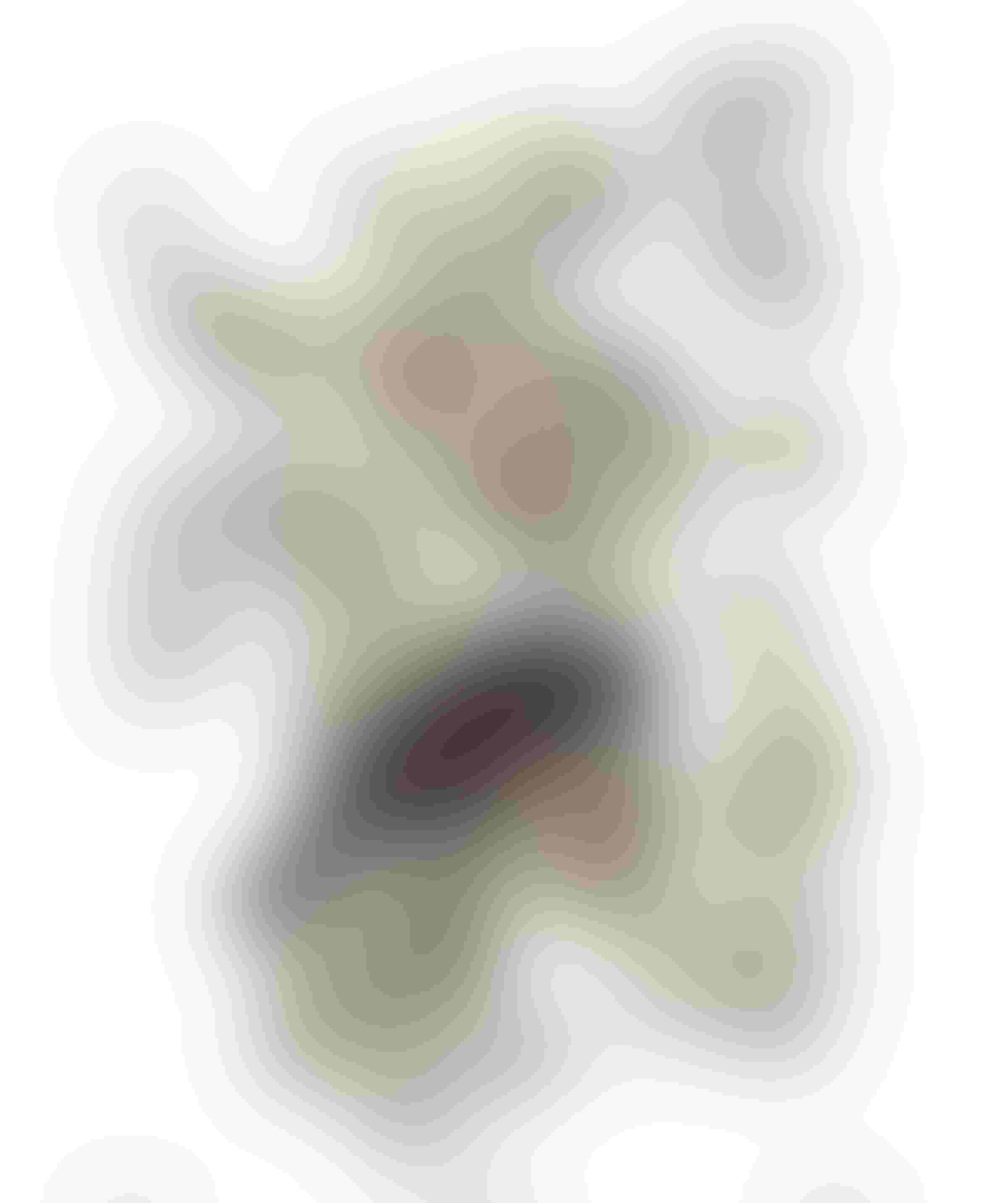

I have placed the pensive oppressed Crow of our country on a beautiful branch of the black walnut tree, loaded with nuts, on the lower twig of which I have represented the delicate nest of our Common Humming-bird.

In conclusion, I would again address our farmers, and tell them that if they persist in killing Crows, the best season for doing so is when their corn begins to ripen.

CROW, Corvus Corone, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. iv. p. 79.

CORVUS CORONE, Bonap. Syn., p. 56.

CORVUS CORONE, Swains. and Rich. F. Bor. Amer., vol. ii. p. 291.

CROW, Corvus Corone, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 209.

AMERICAN CROW, Corvus Americanus, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. ii. p. 317; vol. v.p. 477.

Feathers of the head and neck oval and blended; fourth quill longest; general colour black, with purplish-blue reflections; the hind parts of the neck tinged with purplish-brown; the lower parts less glossy. Young of a rather dull brownish-black, with the blue and purple reflections much less brilliant.

Male, 18, 38.

Generally distributed from the Gulf of Mexico to Columbia river; throughout the interior, and along the coast, northward to lat. 55 degrees. Congregates in immense numbers in the Southern and Western States during winter.

A specimen preserved in spirits measures in length to end of tail 18 1/4 inches, to end of wings 17, to end of claws 16 1/4, extent of wings 35; wing from flexure 12 1/4; tail 1/2; bill along the ridge 2; tarsus 2 1/4.

The palate is concave, with two ridges; the upper mandible internally with five ridges, the lower deeply concave, with a median prominent line. The tongue is 1 inch 2 twelfths long, semicircularly emarginate at the base and papillate, one of the papillae on each side very large; it is horny toward the end, narrow, thin edged, and with the point slit, the fissure being 1 1/2 twelfths in depth. The width of the mouth is 1 inch 1 twelfth; the oesophagus, [a b c d], is 7 inches long, averages 7 1/2 twelfths in width, is funnel-shaped at the commencement, passes along the right side of the neck until it enters the thorax, and has its walls of moderate thickness, with external transverse fibres. The proventricular glands are very small, and form a belt 7 1/2 twelfths in breadth. The stomach, [d e f], is 1 1/2 inches long, 1 inch 5 twelfths broad, of a roundish form, considerably compressed; its lateral muscles large, being about a quarter of an inch thick; its tendons, e, also large and radiating, their transverse diameter 1/2 inch; the cuticular lining thick, dense, of a dark reddish-brown colour, with broad longitudinal rugae. The intestine, [f g h l], forms a curve at the distance of 2 1/2 inches, bends forwards toward the right lobe of the liver, then forms four circular convolutions, and terminates in the rectum. Its length is 29 inches, its width 4 1/2 twelfths in the duodenal portion, and 4 twelfths in the rest of its length; the cloacal [k l], globular and about 1 inch in diameter; the coeca small, [j], cylindrical, 5 1/2 twelfths long and 1 twelfth in breadth.

In another male, the intestine is 42 inches long, from 4 1/2 twelfths to 4 twelfths in width; the coeca 1/2 inch long, and 1 twelfth in width. In a third, a male also, the intestine is 41 1/2 inches long; and in a fourth 33 inches. This statement shews that the intestine of birds sometimes varies very considerably in the same species.

In the stomachs of two of them were numerous seeds of a brownish-yellow colour, globular, and 1 twelfth in diameter, together with a few particles of quartz. That of another contained a mass of pounded sumach berries.

The trachea, [m o], of the first is 5 inches long, a little flattened, 4 1/2 twelfths in breadth at the commencement, 3 1/2 twelfths for 2 inches, near the lower part enlarging to 4 twelfths, and again contracting to 2 3/4 twelfths. The inferior larynx, [o o], is much compressed, with 2 large dimidiate rings. The rings are broad, firm, 56 in number. The bronchi, [o p], [o p], are wide, of about 15 half rings. The muscles are the same as in the Thrushes and Warblers, there being four pairs of inferior laryngeal.

THE BLACK WALNUT.

JUGLANS NIGRA, Willd., Sp. Pl., vol. iv. p. 456. Pursh, Flor. Amer. Sept., vol. ii. p. 636. Mich., Arbr. Forest, vol. i. p. 157, Pl. 1--MONOECIA POLYANDRIA, Linn. --TEREBINTHACEAE, Juss.

The black walnut of the United States is generally a tree of beautiful form, and often, especially in the Western and Southern States, attains a great size. Wherever it is found, you may calculate on the land being of good quality; the wood is very firm, of a dark brown tint, veined, and extremely useful for domestic purposes, many articles of furniture being made of it. It is also employed in ship-building. When used for posts or fence rails, it resists the action of the weather for many years. The nuts are gathered late in autumn, and although rather too oily, are eaten and considered good by many persons. The husking of them is however a disagreeable task, as their covering almost indelibly stains every object with which it comes in contact.

For more on this species, see its entry in the Birds of North America Field Guide.