According to the tracking app on my phone, the cat was in the alley, right in front of me. He should’ve been easy to spot: He’s bright white and, for the past week, he’d been sporting a blue GPS collar, which I’d selected to match his eyes. I peeked behind a dumpster and under a discarded truck topper, but didn’t see him, so I stepped on a junk tire for better vantage into a yard, then froze. I suddenly recalled the previous day, when my similar behavior prompted a passerby to ask suspiciously, “Are you all right?” Flustered, I’d explained I was following a cat, and pointed to—nothing. My feline friend had disappeared.

Reluctant to draw attention again, I stepped back and finally saw him: 15 feet up, perched atop a defunct chimney beside a tree. He glanced at me, sniffed an empty nest, then leapt onto a shed, dropped into a yard with a No Trespassing sign, and padded across the street. I, of course, would have to go the long way around. “Bad Kitty,” I muttered.

To be clear, I wasn’t calling him names. Bad Kitty belongs to my neighbors, who dubbed him Elton upon his adoption, but pivoted when he began swatting stuff off shelves, bringing home dead birds, and arriving at dawn with scratches.

For months I’d wished Bad Kitty would stay inside, away from the irresistible lure of my garden (read: litter box) and bird feeders (snacks and sport). But his outdoor escapades are perfectly legal since, like most towns, Missoula, Montana, doesn’t have a feline leash law. The thought of raising the issue with my neighbor, Jennifer, made me wary. In the past, my in-laws hadn’t appreciated my suggestion that keeping Ethel indoors might be safer for her and birdlife. (Now we stick to less contentious topics, like politics and religion.) To create common ground this time, I pitched Jennifer on following Bad Kitty’s every step for a few weeks with the GPS device, and she readily agreed. It turned out we were both curious about his exploits: I was mostly interested in his impact on wildlife, while Jennifer was concerned about his safety.

I knew I was wading into one of the thornier issues in conservation. America’s roughly 100 million free-roaming felines—about one-third pets, the rest abandoned, stray, or feral—aren’t native to any ecosystem they prowl, and the skilled predators hunt a wide array of wildlife. In other such cases, government agencies often try to control or eliminate introduced species that pose ecological, public health, or economic threats. Florida, for example, has hired bounty hunters to humanely kill Burmese pythons, which devour native wildlife. However, scientists and conservationists have found that people don’t view 16-foot snakes as they do creatures that purr when petted and have a long history of roving as they please.

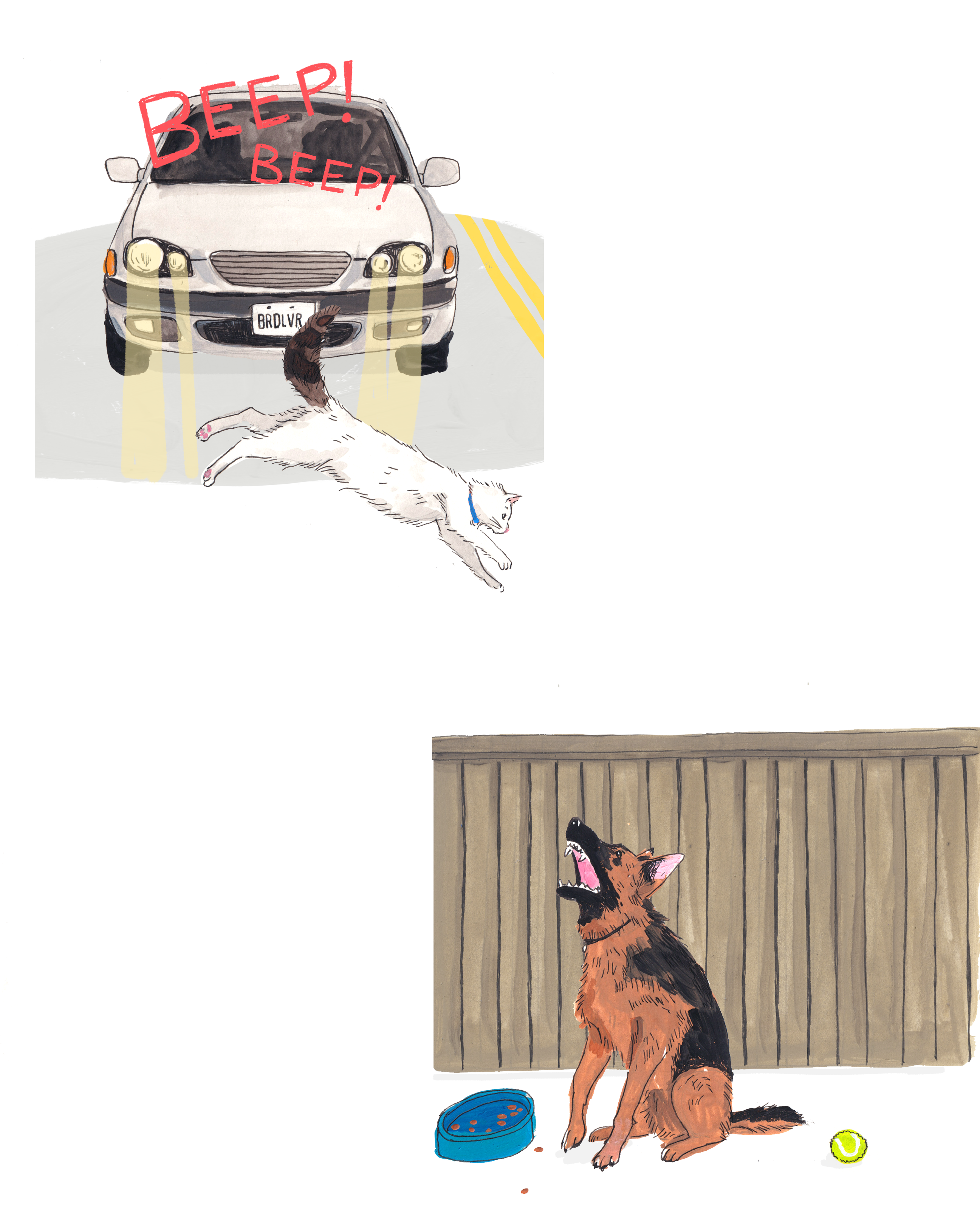

Our feline companions’ freedom is such a deeply ingrained quirk of the social contract that even our other favorite pets get far more rigid treatment. Every state requires dog licensing, leash laws and anti-roaming regulations abound, and violations can carry fines. When Jennifer’s dogs escaped her yard, I texted her and she collected them. When I see Bad Kitty leave scat or robin remains, I sigh and dispose of them.

Dogs, too, were once largely unrestricted, but over time public sentiment changed and policies followed. No longer giving Bad Kitty and other cats the run of the place would be a significant cultural shift. What, I wondered, would it take for us to treat Fluffy as we treat Fido?

From a puff-ball Persian to an inscrutable alley cat, the domestic felines that dominate the internet today began their worldwide spread from a common ancestor nearly 10,000 years ago. In the Fertile Crescent region, rodents that devoured grains likely drew African-Asian wildcats to settlements, and people welcomed the vermin control. Ancient Egypt, where cats became treasured pets, saw a second wave of domestication, and Romans later spread them to Europe. During colonial expansion, shipboard cats protected food stores and proliferated nearly everywhere sailors landed. Today cats inhabit every continent except Antarctica, and they’ve left their mark on ecosystems far and wide. They’ve been linked to the global extinction of at least 63 species—40 birds, 21 mammals, and 2 reptiles—all on islands or in Australia, which have few, if any, native mammalian predators. Their presence threatens the survival of at least 367 other species.

In the United States, pet cats date to the late 19th century, when they were useful as mousers in booming cities. At the time, spaying and neutering were rare, and kittens were often abandoned to fend for themselves. Soon scientists wondered how birds were faring in an increasingly catty world. In a 1916 report, ornithologist Edward Forbush painted a grim picture: Vagrant cats abounded—in the previous decade, more than 210,000 had been euthanized in Boston alone—and nearly all pets roamed at night, allowing the crepuscular creatures to hunt when they prefer.

The first national catfight ensued. Scientists and conservationists were alarmed by the threat to songbirds, which kept crop-destroying insects in check before the wide use of pesticides. Many avian species were also newly protected under the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act. “Probably none of our native wild animals destroy as many birds as do cats,” said Henry Henshaw, head of the precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Cat lovers, meanwhile, accused avian proponents of hysteria and balked at recommendations to confine felines during nesting season, especially at night. In the 1930s, the National Association of Audubon Societies launched a cat licensing campaign, reasoning that people would keep fewer felines due to the cost; they didn’t, and in 1933 the organization lamented the reluctance of city officials to take up or enforce cat-restrictive measures.

Cats began living inside gradually, though wildlife worries weren’t the reason. With scratching posts available at pet stores in the 1930s and commercial kitty litter hitting supermarket shelves in the 1950s, cats became less destructive and malodorous housemates—and with improved access to sterilization, less noisy ones, too. (Unsterilized cats yowl and spray urine throughout their roughly eight-month mating season.) Concerns about the welfare of outdoor pets and strays were also growing. When a startling statistic that overburdened shelters were euthanizing 13.5 million animals annually—a significant portion of them cats—made headlines in the 1970s, the Humane Society of the United States and other animal groups began encouraging more responsible pet ownership to curb the creation of more kittens.

By then, there were some 30 million pet cats in the United States, and people were also recognizing that every paw step outside is perilous. Outdoor cats are more prone to illness and are vulnerable to attacks from other cats, dogs, coyotes, and raccoons. They might lap up toxic antifreeze, become poisoned by a mouse laced with rodenticide, or freeze in a winter storm. On average, outdoor cats live far shorter lives than their housebound kin. What’s more, they can also transmit diseases, including rabies and the plague, and their scat can carry a parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, that exerts a sort of mind control on mice by stripping them of their fear of cat odors, making them easy prey. Humans can be infected with it, too: 1 in 10 people in the United States have toxo, most to no obvious effect. But the parasite can cause stillbirth, miscarriage, or even death in immunocompromised individuals, and new studies show a link between infection and schizophrenia, depression, and risk-taking behaviors.

To a growing number of pawrents, the answer is simple: Keep Pearl under lock and key, as 63 percent of cat owners now do. That number is up from 35 percent in the 1990s; around that time, more municipalities across the country began to enact cat licensing laws and pass ordinances that limited felines on the landscape, spurred by animal welfare concerns and two highly publicized studies pointing to a massive avian death toll.

Yet such laws are rarely enforced. And the cat population has more than doubled in the past half century. That means more cats than ever may prowl the outdoors.

Between naps, Bad Kitty chases squirrels across my roof, scales a three-story fire escape, crisscrosses streets, hunkers under parked cars, and strolls atop fences, indifferent to growling dogs. He frequents a mouse-y schoolyard dumpster and meets up with a tabby frenemy; they either screech and part ways or sit side by side, tails twitching, fixated on a neighbor’s feeder. I’ve spotted Bad Kitty batting a Dark-eyed Junco, carrying a pigeon homeward, and nearly nabbing a Northern Flicker. To find him, sometimes I’ve simply homed in on Black-capped Chickadees belting an alarmed chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee-dee or squirrels barking kuk kuk kuk kuk.

After the flurry of laws in the 1990s, conservationists largely considered the cat situation handled, says Christopher Lepczyk, an Auburn University ecologist: “They said, ‘We’ve given you the evidence; you’ve done something; we have other problems we need to talk about.’” In 2013, ornithologist Peter Marra and his colleagues found that the problem hadn’t gone away. Far from it.

They reviewed existing studies and calculated that cats kill at least 1.3 billion birds and 6.3 billion mammals annually in the United States. After habitat loss and fragmentation, those mind-boggling figures made outdoor cats the number-two cause of avian mortality, deadlier than building and wind turbine collisions combined. “Outdoor cats are contributing to the unraveling of the complex, interwoven web of species of plants and animals that make up nature,” says Marra, dean of Georgetown University’s Earth Commons Institute and coauthor of Cat Wars: The Devastating Consequences of a Cuddly Killer.

The study generated an uproar unusual for a scientific paper. Alley Cat Allies, a cat advocacy nonprofit, delivered a petition with 55,000 signatures to the Smithsonian Institution, Marra’s employer, denouncing the results. The group wasn’t convinced that outdoor cats killed so much wildlife or had a significant environmental impact.

Yet finding after finding continues to place paw prints all over the ecological scene. I got the idea to track Bad Kitty from North Carolina State University zoologist Roland Kays, who worked with scientists and cat owners to uncover the secret lives of 925 felines in six countries in 2020. The pets rarely traveled more than 0.2 miles from home (ditto for Bad Kitty) but killed up to 10 times more animals per acre than native carnivores. “Because they’re using such small areas, it really concentrates their hunting,” Kays says. What’s more, cats far outnumber coyotes, foxes, and hawks. As a result, the average bird is more likely to be killed by a cat, even though each individual native predator takes more prey over a larger area.

Offering kibble isn’t a solution. While not all pet and feral cats fed by people hunt, many do—even when they aren’t hungry, studies show. Owned felines, in particular, leave a lot of prey uneaten, says Martina Cecchetti, a companion-animal ecologist at University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Conservationists want to know which species cats kill and are especially concerned about impacts on sensitive populations. “Are they eating abundant, introduced animals?” asks Claire Nemes, an avian ecologist at University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science. “Or endemic wildlife? Or migratory birds?”

Much of the information about what cats kill comes from owner surveys, which don’t capture the full picture. Kitty camera studies have found that the occasional carcasses that Tucker and James bring home represent only about a quarter of their quarry. (Sorry, owners: Your cat isn’t presenting that dead sparrow to you. “It’s not a gift,” says Cecchetti; like a wildcat, he’s caching his catch.)

To deliver more data and pinpoint when birds are most vulnerable, University of Guelph ecologist Ryan Norris launched a large-scale camera study. The cat’s-eye view is revealing that not all felines are killers, and a rare few are exceptional assassins. Some hunters stalk various birds, small mammals, and insects; others are picky eaters. “We’re finding huge variability in what cats do,” he says.

Ultimately, Norris aims to refine cat predation estimates across the continent and create a database of which species are hit hardest and when, which might reinforce keeping cats inside at least during those times. In Puerto Rico, Nemes is taking a different approach to determining their diet by analyzing the DNA in scat. This local snapshot might reveal whether cats are preying upon endemic species, migratory species that stop over or winter on the island, or other vulnerable wildlife.

Getting more accurate feline population numbers is another key to better understanding their impact, though herding cats might be easier than counting them. In 2018, scientists and animal welfare groups in Washington, D.C., wanted to create better census methods. Three years and $1.5 million later, they’d deployed 1,530 cameras, surveyed shelters and households, recorded felines along designated routes, and tallied some 200,000 cats, more than half of which always stay inside. Now, thanks to the cat-counting tool kit, other cities don’t have to start from scratch.

While such data help pin down nuances of the problem and guide more targeted solutions, scientists I interviewed said there’s no question that outdoor cats pose a serious environmental threat. “We don’t really need more evidence,” Lepczyk says. “Society really struggles with: At what point do you stop doing research and move the needle on policy or management?” The Humane Society and PETA acknowledge that cats are a significant risk to wildlife and should be kept indoors. But plenty of people still believe cats can’t be content inside, and influential advocacy groups continue to maintain that the compassionate option is to let them roam; Alley Cat Allies insists these nonnative animals are a natural part of the landscape.

To Nemes, who has four rescue cats, it’s analogous to the climate change debate: “You can give people all the facts, but a lot of times science alone doesn’t convince people. We need to understand what their concerns are to find alternatives that are humane for cats and wildlife.”

On a sunny fall day, I joined 1,000 attendees for a tour of homes in Portland, Oregon. Instead of goggling stunning interiors, we perused outdoor cat enclosures. I wasn’t sure what to expect at my first stop on the Catio (a.k.a. cat patio) Tour, but it wasn’t a tiki-themed oasis. “We sit out here for hours with them,” Debbie Orozco told me, introducing me to Otto, Cosmo, and Nanala. She and her husband built the structure after a previous tour. They’d kept the trio indoors since moving to traffic-filled Portland, much to the cats’ initial displeasure. Now the felines nap away warm days and watch birds flit about, safely out of reach.

The Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon (FCCO) and the Bird Alliance of Oregon (an Audubon chapter) started the tour in 2013 as part of their joint Cats Safe at Home program, which works to humanely reduce outdoor cat populations. The structures, which come in all shapes and sizes, have since gone mainstream. “Catios have been covered in Martha Stewart Living,” says Bob Sallinger, Bird Alliance of Oregon’s former conservation director. As catios continue to pop up around towns and in popular culture, people may start to think differently about what responsible cat ownership looks like, says Sallinger, who is now executive director of Bird Conservation Oregon. These days, several cities host similar tours organized by groups with a shared concern for animals. “Every feral cat that’s out there, its lineage goes back to a pet,” says Karen Kraus, executive director of FCCO, which aims to reduce unowned cat populations through sterilization and education. “If there are fewer stray cats, there will be less predation and fewer future ferals.”

The most convincing argument for keeping cats inside is their welfare, advocates say: It resonates with Leo’s owner that he’s safer inside. Catios are just one way to give felines an outdoor fix, says Grant Sizemore, who runs the American Bird Conservancy’s Cats Indoors program. Like dogs, they can be leash-trained. Too hard? Pop Adobe in a stroller or backpack. Supervise Grackle outside, or install cat-proof fencing. Inside, satisfying Tomato’s instinct to hunt can help stave off boredom, anxiety, and agitation. “The cat knows it’s not going to eat a feather toy,” Sizemore says. “But they’re still engaging in the exact same behavior that would be lethal outside.” Ten to 15 minutes of play twice a day will keep most cats fit and stimulated. And conveniences like automatic feeders and self-cleaning litter boxes make ownership easier than ever.

Everyone I interviewed agreed that keeping cats indoors is best for wildlife and their own safety. Barring that, some noted that poofy colorful collars visible to birds might curb cats’ kill rates (bells are largely ineffective). And Kays’s Ph.D. student Mohammad Alyetama is developing a collar that emits an avian alarm call when a feline starts hunting. The gadget could save lives, but a cat’s mere presence can also cause harm, disrupting breeding and foraging.

Unowned cats are an even trickier subject. Following the science, many U.S. conservationists would like to see colonies removed: Healthy, sociable cats would be adopted out, and those too sick or feral would be housed in sanctuaries or euthanized. Passing and enforcing license laws, outdoor feeding bans, and roaming restrictions would likely further reduce populations. Versions of such policies have gained ground elsewhere: In Iceland, several towns require cats to be inside at night or always, and Walldorf, Germany, bans roaming when Crested Larks breed. Australia, meanwhile, is removing all feral cats from the landscape.

But in the United States, trap-neuter-return (TNR) programs, where cats are sterilized and released back to their colony, have advanced. Several groups argue it’s the humane way to reduce unowned cats. In the past two decades, cities including Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Miami have adopted TNR, aided by funding from pet food companies. Alley Cat Allies and Best Friends Animal Society vehemently oppose any lethal control and have successfully encouraged municipalities to legalize “community” colonies, as they call them, and allow inhabitants—identifiable by missing ear tips, removed during TNR—to be at large. Across the country, thousands of colony caretakers fill food and water bowls and provide insulated boxes to help cats survive winter.

Despite its popularity, TNR has rarely worked. Far from diminishing cat populations, it may be exacerbating the problem by encouraging people to abandon pets, knowing they’ll be cared for in colonies. For TNR to be effective, at least 75 percent of a colony has to be sterilized and new cats can’t join. “That rarely happens in an open system,” Marra says. The group PETA agrees that the practice isn’t a solution: “TNR makes humans—not cats and certainly not wildlife—feel better.”

One place TNR hasn’t made inroads is state and federal agencies: None use or endorse the practice. On public lands, wildlife managers focus on removing cats from biologically important areas—though they tend not to publicize it, Lepczyk says. After Florida’s Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge was rid of cats and Burmese pythons, for instance, endangered Key Largo woodrats increased quickly. “Predator control is very effective, but you have to do it year in, year out,” says André Raine, science director of environmental consulting nonprofit Archipelago Research and Conservation. “New cats just keep coming.”

In Hawai‘i, cats that come knocking at some seabird colonies increasingly can’t get in. Agencies and organizations, including Raine’s group, are installing tall fences with curved tops that cats can’t scale. They’re expensive, but effective: The largest safeguards more than 600 acres of nesting habitat of the endangered ‘ua‘u, or Hawaiian Petrel, on Mauna Loa. Since its completion in 2016, endangered ʻakēʻakē, or Band-rumped Storm-Petrels, have also been breeding there.

Raine, himself a cat owner, understands why people have sympathy for cats, but says most don’t see the devastation they cause: “When there’s no management, there’s just dead birds everywhere.”

In a move that might herald a larger shift on public lands, the National Park Service is permanently removing all cats from San Juan National Historic Site in Puerto Rico, citing concerns about feline-borne disease. The agency will hire an animal welfare group to take away feeding stations and find homes or shelters for the estimated 200 felines, and then contract a removal agency to euthanize any remaining after six months. Unsurprisingly, the decision caused a stir, but the agency isn’t backing down.

Ten years ago, seeing a cat on a leash or in a stroller might have stopped most people in their tracks. In the past few weeks alone, I’ve seen harnessed felines walking through an airport, in the woods, and on a circuit around my neighborhood—not to mention on countless TikTok accounts.

And more towns are treating cats like dogs. Denver is actively encouraging owners to comply with licensing laws. Swelling populations have led Cary, North Carolina, to begin enforcing leash laws and Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i, to ban feeding ferals on county property. Amid public complaints of unowned cats being an unsanitary nuisance, in January, the Strasburg, Ohio, city council said it was considering a ban on providing food or shelter for feral or stray cats; one resident told a news outlet he supported the measure for fear that his neighborhood was “just going to turn into one big litter box.”

As for Bad Kitty, he’s still roving, but not quite as freely. My furry neighbor is the family’s first cat, and the shelter said he’d previously roamed outside. Jennifer let him out after two frenetic weeks indoors. He seemed happier, she says, and there were other advantages: “He rarely uses his litter box.” (I died a little, thinking of my garden.)

When we discussed his GPS tracks, Jennifer was concerned about how often Bad Kitty crosses the street. And she was alarmed to learn coyotes wander our neighborhood (frequent “missing cat” posters are no coincidence). “What I’d really like is a catio,” she said before I ever uttered the word, pointing to a narrow patch of yard where she may build one someday. For now, Bad Kitty stays inside at night, and outside he sports a Birdsbesafe rainbow-patterned collar. He looks like a clown, but Jennifer likes that he’s more visible to cars and that so far he’s stopped bringing home birds. If not exactly the outcome I’d hoped for, gaining a better understanding of where we’re each coming from feels like progress.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2024 issue as “Where the Not-So-Wild Things Roam.” To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.