Researchers have just scrambled a long-held belief about eggs, one that could make biologists reconsider which birds are the true reproductive champs.

Traditionally, biologists have measured reproductive investment—the amount of effort a bird puts into procreation—by the number of eggs in each clutch. The higher the number, the bigger a bird’s investment was assumed to be. But that approach carries limitations. “This measure is quite coarse and ignores many other aspects of variation in breeding effort,” says Watson.

In a new Plos One paper, David Watson and his colleagues took a different tack from other ornithologists and measured total clutch volume instead of egg numbers alone. To do this, they studied the eggs of 1,364 species, randomly selected from 204 avian families. “We calculated the volume of an egg and multiplied that by the average number of eggs laid in a clutch,” Watson, who is an ecologist from Charles Sturt University in Australia, explains. “In basic terms, this equates to the amount of ‘stuff’ a female bird produces in a reproductive bout, and is sensitive to changes in both the number of eggs laid and their size.” This technique allowed a more refined—and somewhat fairer—measurement of the effort different birds really put in to making their eggs.

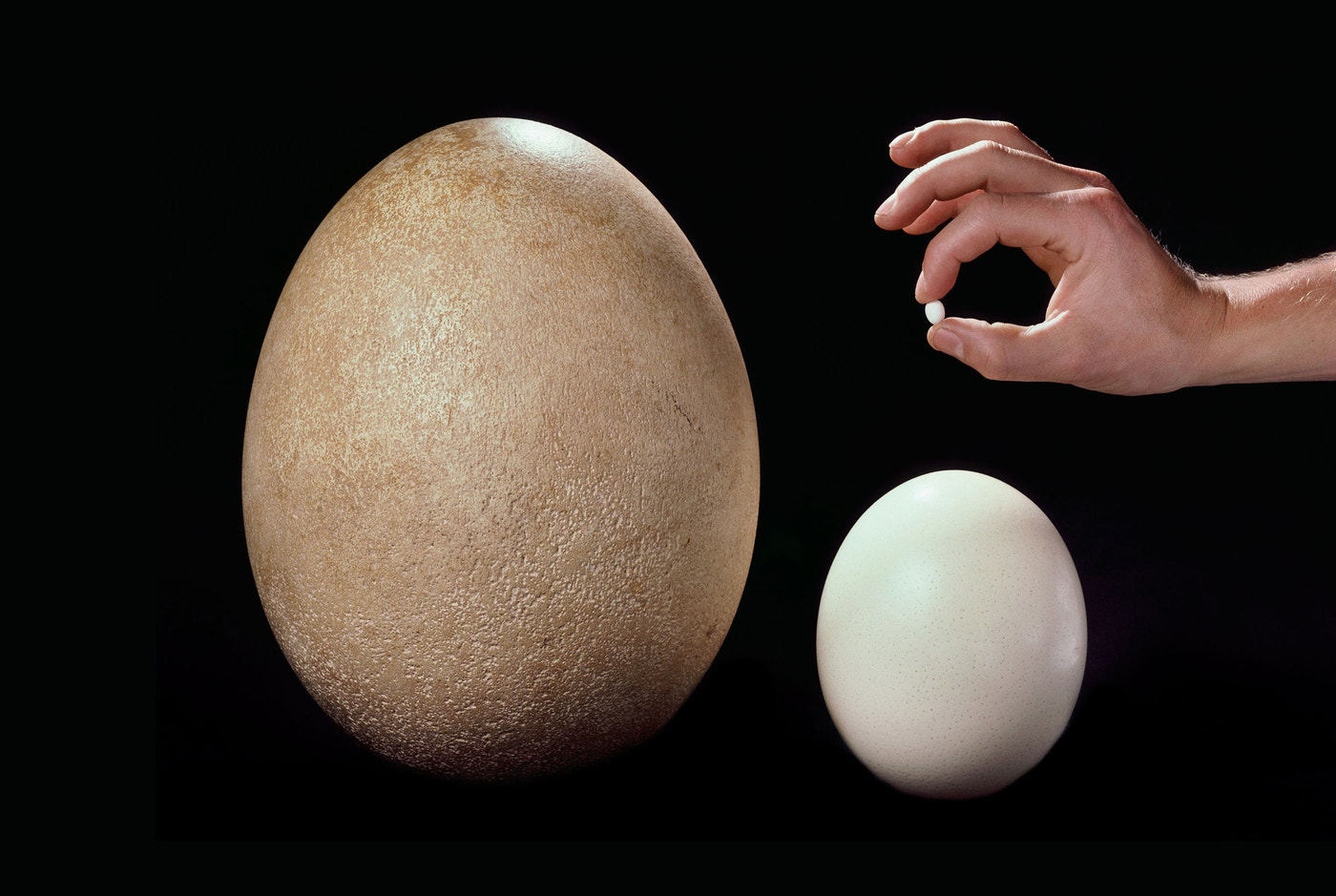

At first, Watson and his colleagues generally found a strong relationship between body mass and reproductive output. This pattern seems intuitive: Big birds tend to lay bigger eggs (as illustrated in the photo above), and more of them as well. But the team then made an unexpected finding that showed this isn’t true for all avians.

Megapodes, which include 19 chicken-like birds such as scrubfowl and Brush-turkeys, are able to produce a clutch that has the same volume as birds seven times their mass. They are known for laying large quantities of giant eggs. But no one realized just how huge their reproductive investment is relative to their size, until Watson made the calculations. “The average clutch volume of this family far exceeds that of any other group of birds,” Watson says. “This is a novel result, never before found or even suspected.”

With this new method, the megapodes have surpassed birds like the kiwi, a family long lauded for its enormous eggs. “The fact that [kiwis] package all of this 'stuff' in a single massive egg rather than a bunch or regular-size ones has long fascinated biologists. But we have demonstrated it’s just a different way of investing the same effort, not a disproportionately large investment,” Watson says. (He adds, however, that comparing individual bird species was beyond the scope of the study, which focused only on families of birds.)

So how can megapodes afford to devote so much energy to reproducing? “These birds are the only group that does not use body heat to incubate their eggs, and they exhibit no parental care after the eggs hatch,” Watson says. They’re unique because instead of relying on their own mass to incubate their eggs, megapodes channel heat from their nest materials: warm sand, soil near volcanic vents, or humid piles of rotting vegetation. In other words, the bird’s small mass doesn’t limit its ability to churn out lots of large eggs.

Now that megapodes have received the credit they deserve, it's time to reconsider if size really matters.