On a late spring morning in October, in a spotted gum-ironbark forest he describes as “dry as toast,” BirdLife Australia’s Mick Roderick and I are on the lookout for Regent Honeyeaters. While the area we walk has thus far avoided total ruin from cataclysmic bushfires, the tinder-dry leaves beneath our boots send the clear and crackling message: This could all go up in a flash, and with it the future of one of the country’s most iconic woodland birds.

We met earlier near a billboard that features a worn, discolored map offering these grounds as investment property. But the real value, Roderick says, is found in the diverse ecosystem that has built up over millennia in this 3.4-square-mile remnant of Lower Hunter Valley woodland in eastern Australia. Away from the main road, the forest is full of birds—a flock of White-browed Woodswallows veering over the treetops, a pair of Black-chinned Honeyeaters knifing through the leaves, the steady whistles of Little Lorikeets. But a Regent Honeyeater? This most charismatic of Australia’s woodland birds, with black chainmail-like patterns on its breast and long lemon-yellow tail feathers, is an exceedingly rare sight.

The steady loss, degradation, and fragmentation of the Regent’s habitat over the past century have pushed this brilliantly colored bird to the edge of extinction. But it’s fire, intensified by ever hotter temperatures and ever lower rainfall, that unnerves Roderick most. “Every summer comes around and I’m like, ‘Oh god, here we go again,’ ” he says. “If all the unburnt patches go up, then we’ll essentially be writing off the honeyeater’s habitat.” And, though he doesn’t say it, the bird itself.

Roderick and his collaborators, including a local Aboriginal community, have made a remarkable effort to save the Regent Honeyeater, BirdLife Australia’s flagship woodland species. That work, highlighted by the recent release of a flock of captive-bred birds, seems to be paying off—and to the benefit of far more than the critically endangered species. Protecting Regents helps safeguard a whole suite of other birds in decline that depend on the same landscapes, like the Speckled Warbler, Dusky Woodswallow, Turquoise Parrot, and Diamond Firetail.

Still, says Roderick, “In the back of my mind I wonder, ‘Is this all in vain?’ ” It’s a question many in Australia’s bird conservation community are asking in the wake of drought, floods, COVID-19, and a devastating bushfire season—one that was both the most severe in memory and also a harbinger, scientists say, of fire seasons to come.

F

or 19th-century ornithologist John Gould, the Regent Honeyeater was wonderfully present, appearing in flocks of 50 or more: “I met with it in great abundance,” he wrote in his 1848 book, The Birds of Australia Vol. 4. As recently as 1980, a bird guide labeled the species “fairly common.” But this status was overly optimistic. Since the 1960s the population has been in a free fall. Today fewer than 400 individuals exist in the wild, spread over a geographical region roughly the size of France.

This vast range reflects how far the nomadic bird must fly to find the patches of flowering trees that are vital to its survival—such as ironbark, box, and gum—and that have become greatly fragmented as woodlands have been cut down to make way for development. Take, for instance, where we stand this morning, in one of the Regent’s last known strongholds: the Hunter Valley, which runs northwest from near Australia’s eastern coast for about 100 miles. Only about one-third of the valley remains undeveloped since Europeans first arrived more than two centuries ago, and of this, only five percent of the fertile central valley floor—the only breeding habitat for woodland birds—remains intact. Most of the undeveloped tracts that remain have been torn into 10- or 20-acre scraps, not nearly large enough to serve as breeding habitat for most forest-dwelling birds, let alone specialists like Regents. “All these threatened woodland birds are headed in the wrong direction,” says Ross Crates, an ornithology postdoctoral researcher at the Australian National University (ANU). “It’s just that Regents are the quickest in that direction.”

On this October morning, Roderick and I are walking through what he tells me is the most significant woodland remnant on the valley floor, the Hunter Economic Zone (HEZ). Due primarily to poor planning, this developer’s fantasy of a huge industrial park has in its two decades yet to materialize beyond an aluminum-extrusion plant and a single paved “road to nowhere.” But its woodlands remain fantastic bird habitat.

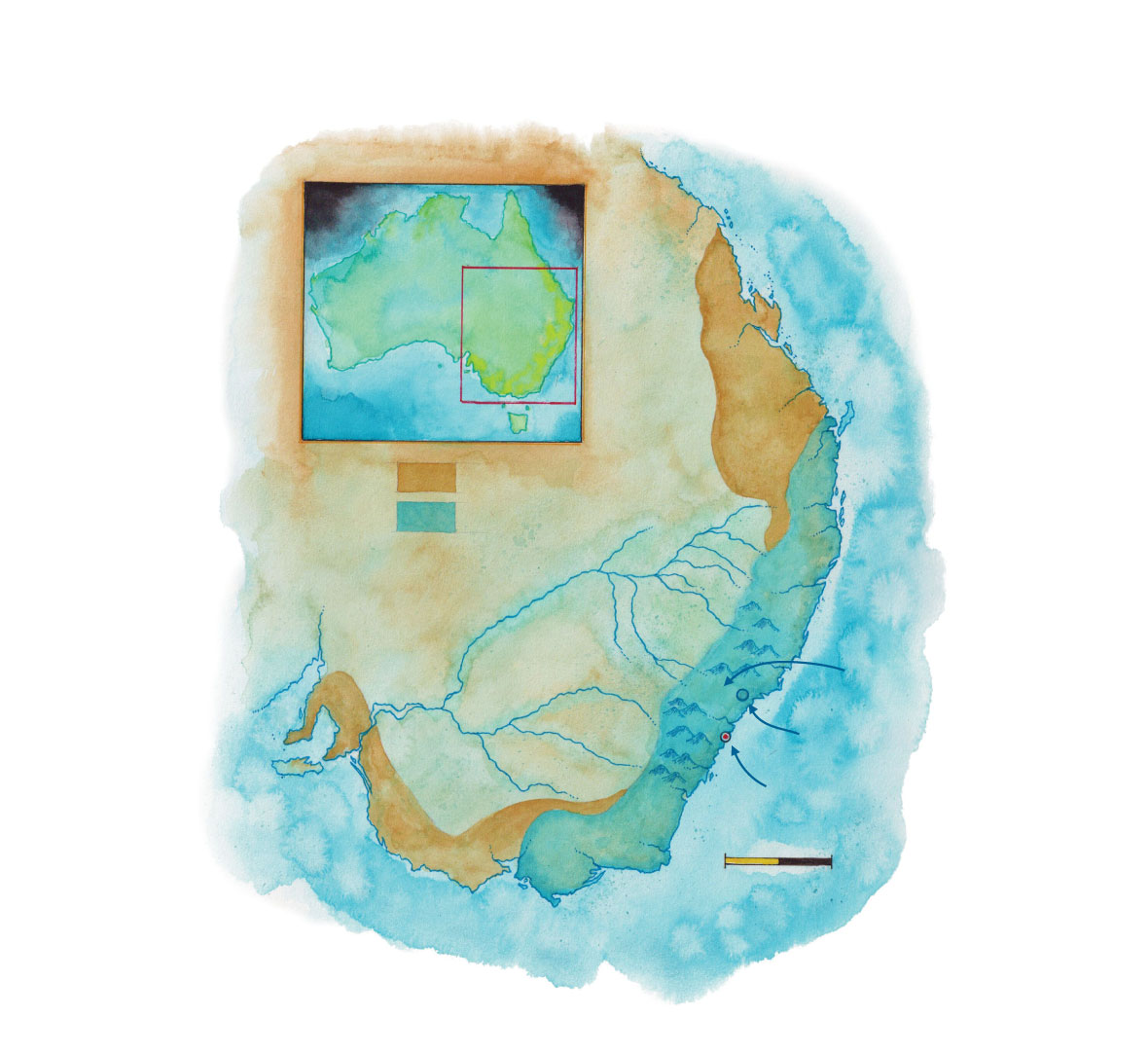

Regent Honeyeater Range

AUSTRALIA

HISTORIC RANGE

PRESENT RANGE

HUNTER

VALLEY

BLUE MTNS

HUNTER

ECONOMIC

ZONE

SYDNEY

MILES

0

300

TASMAN SEA

MAP: MIKE REAGAN

In 2018 HEZ was the only place scientists found any Regents. “We monitor more than 1,000 sites from Northeast Victoria to Southeast Queensland covering the breeding range,” says Roderick. “We could barely find a bird, let alone find them breeding.”

It’s within the last few larger remnants of this valley floor woodland habitat, such as the nearly 2,200 acres of HEZ, that birds like vulnerable Speckled Warblers and endangered Swift Parrots concentrate. “It beggars belief that they would even consider putting an industrial estate here, because it’s just so incredibly valuable from a biodiversity perspective,” Roderick says. In some years, he adds, “These birds have nowhere else to go.”

Ironically, this swath of habitat remains intact because of the same industrial forces that have so negatively impacted other locations. For decades these woods were kept as a timber reserve for underground coal-mining operations, the felled trees used for ceiling beams and wall supports. After a downturn in mining, the area was zoned industrial and remains so, a fact that exasperates Roderick. “As long as that zoning is here, we can’t relax. About six years ago, they wanted to put an ammonia-nitrate storage facility in here,” he says, explaining that similar projects surface from time to time. “But I mean, this place could qualify for World Heritage status with the diversity of eucalypts alone.”

As we talk, a flock of chestnut-gray birds passes overhead. “These White-browed Woodswallows are a migratory bird. Very mobile, they travel in big flocks, and they only breed where the best habitat is,” says Roderick, “and they come to HEZ. So, it’s not just us saying HEZ is important. These birds are telling us, too.”

Clearly, conservationists have been listening. So, too, have the area’s new principal landowner, the Mindaribba Local Aboriginal Land Council (MLALC), which is comprised of very old communities of Indigenous people, newly empowered.

A

s part of Australia’s reckoning with its often brutal past, much of HEZ was recently returned to the Indigenous people from whom it was stolen. The invasion by white settlers, beginning 232 years ago, resulted in “almost total annihilation” of the local Wonnarua people, says Tara Dever, a Wiradjuri woman and CEO of the MLALC; the state government allowed Aboriginal people back onto this land only three years ago. As one of the few places in the Hunter Valley that still resembles what it was two centuries ago, HEZ is culturally invaluable. Aboriginal Australians have always seen themselves as part of the country, a term that encompasses all living things, including people. The trauma of being torn from the country still lingers, Dever says, and having control of this place is a vital step toward both healing the past and embracing the future.

As a result, developing HEZ doesn’t interest the Mindaribba community. When I ask about a recent proposal for two Chinese-financed coal-fired power plants, Dever sighs. “There’s lots of talk about people coming in and building, and I find that pretty amazing, because we own the one road in, we own most of the land. I don’t know where you’re putting it,” she says. “This community wants to care for that area. This community is very, very concerned about there not being an opportunity for our children to even look at a tree, let alone a Regent Honeyeater.”

That said, the community will decide for itself how to use the land. “The fact that there are these amazing birds out there that are critically endangered is secondary to what we would choose to do as sovereign people in caring for that country,” Dever says. For example, she would like to see the Mindaribba employ fire-stick farming—a traditional land-management practice that uses prescribed burns—and eventually grow traditional foods to help the community become self-sustaining. She also hopes to develop a small ecotourism operation that could draw international birders interested in combining their search for woodland birds with learning about the Aboriginal people and their relationship with the landscape. “We need to have the means to house and educate,” she says, “but we need to protect, too.”

Most recently, the community has allowed BirdLife on its land to restore the mistletoe that grows in gum trees’ upper reaches. A plant that depends on the aptly named Mistletoebird to disperse its seeds, the mistletoe helps sustain dozens of bird species. But unlike many native plants, it doesn’t regenerate after fire. “Much of where the Regent Honeyeater has traditionally bred and fed across eastern Australia has been annihilated by fire,” Roderick says of recent years, “and they’ve been such high-intensity fires, they’ve incinerated some of the mistletoe.” In badly burnt areas of HEZ, BirdLife is seeding gum trees with mistletoe fruits—the first time the approach has ever been taken in the region.

“If they can’t breed in HEZ, they may not have options elsewhere,” Roderick explains. That could be disastrous for the species, given its small population and the fact that Regents live only 6 to 10 years. “It’s a numbers game, and the Regent Honeyeater simply cannot afford to miss a breeding season.”

The wild population got a significant boost in June, with the release of 20 captive-bred birds on private land near HEZ. Since the Regent captive-breeding program began, at Sydney’s Taronga Zoo in 1995, scientists have released 285 birds in southern Australia. The June event was the first major release in New South Wales, at a site the recovery team thought would be ideal because it’s in the middle of the species’ range, with abundant, budding spotted gum and stringybark that could provide plenty of nectar for the birds. If wild Regents did show up, they figured, the captive-bred birds would have the opportunity to assimilate with the wild flock, and then move together come breeding time.

Roderick is optimistic that BirdLife will be able to follow the released birds, thanks to radio transmitters 13 are sporting. What he really hopes for, though, is the eventual use of satellite transmitters, a technology that is still a few years away for the Regents. These could help to unlock the mystery of where Regents go each summer, something those involved in the recovery effort can only guess at now and information that could help focus conservation efforts. “The holy grail for the Regent Honeyeater knowledge bucket is where do they go after they breed. We have no idea,” he says. Speculation has the Regents moving into the largely inaccessible high country in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney between breeding time and when their favorite trees begin to flower.

This recent release of captive-bred Regents was all the more meaningful because it had been more than three years since the last release. One had been scheduled for last year, but drought conditions at the release site were so extreme that the recovery team decided it wasn’t worth the risk. That proved to be a smart choice. Fire ripped through the area just months later.

Use the arrows to scroll through the gallery below.

B

ushfires have long been part of life in Australia. But in talking with Australians involved with conservation, I got the sense that last season was different. The fires tore through huge areas of the country and, according to the most recent estimates, killed or displaced nearly 3 billion mammals, birds, frogs, and reptiles. They signaled a new reality, rather than representing simply a particularly intense example of something very old.

What made these fires unique, says Sarah Legge, a wildlife biologist at ANU, was that they affected such large areas at the same time. For birds, that meant the habitat they would normally flee to during or after such fires wasn’t available. “With low-intensity fires, the birds just kind of keep ahead of the front and then pop over the top and go back to where they were before,” she says. “But these fires moved so fast and burned so hot that a lot of birds would have died. Even the ones that would have survived faced an enormous resource bottleneck lasting, potentially, many months.” For all of the country’s fauna, she says, such fires are a worrying prospect. “Homing in on species that were already on the brink, this kind of event can be enough to push them over the edge.” She cites the Rufous Scrub-bird, a range-restricted habitat specialist of an ancient evolutionary lineage, which had as much as 52 percent of its habitat burnt. “For birds like that,” she says, “their future looks pretty bleak.”

Last year was the hottest year on record for Australia, and also the driest. Long-term trends have for several years shown more frequent fires and longer fire seasons around the world, including in California, where devastating conflagrations erupted in August. But nowhere is the phenomenon more existentially significant for wildlife than in Australia. Experts say that all signs point to catastrophes on the scale of last year’s events occurring more frequently.

Asked if the reality of the situation has shaken the conservation community, Legge says many of her peers have been struggling with the idea that one huge event might overwhelm years of intensive work. “You think, ‘What was all the effort for?’ Over the Christmas period I’d get up early and look at the news every day,” she says. “I’d just sit there and cry for a few minutes at the enormity of it all.”

G

lenn Albrecht understands this emotion intuitively. An environmental philosopher and lifelong bird lover who lives not far from HEZ, Albrecht gained global attention for his concept of solastalgia: the homesickness you feel when you’re still at home, due to environmental change. He says the impact from last season’s fires is likely to be a permanent one. “I think the awareness of the scale and ferocity of the instant change of the landscape has now kind of burnt a bit of solastalgia into everyone,” he says. “Even if they don’t know the meaning of the word.”

It’s a feeling that seems likely to spread as droughts and wildfire intensify. Australia’s birds, meanwhile, will experience their own disorienting condition—“total koyaanisqatsi,” he says, using the Hopi word meaning “life out of balance.” “There’s just going to be a lot of confused birds. They’re not going to know what the hell’s going on, because all of the patterns and rhythms of the past are being disrupted. You can see that happening all over the place.” Scientists in Australia have already documented shifts in timing for migration and breeding. For critically endangered species like the Regent Honeyeater, these changes could be one stressor too many.

The notion of solastalgia resonates with Ann Lindsey, a volunteer and activist on behalf of Hunter Valley birds for three decades. “I really feel very sad at our changing landscape all of the time,” she says. “You go to places that have been chopped down, or there’s a coal mine there, or a there’s a proposed coal mine there. And now these fires? I can hardly bear to think of it.”

When discussing the emotional toll of the fires, Roderick asks if I know Aldo Leopold’s words from A Sand County Almanac: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.” For him, this describes solastalgia, and he says friends who don’t know how much work has gone into the recovery program and how devastating the fires have been “don’t quite understand how it gets to the heart of our bond with nature.”

We have a choice, Leopold went on to write, to either ignore what we see happening or do what we can to address it. For everyone I spoke with in Australia, the choice is clear. “We think that around 30 percent of the Regent’s range burned last season, and something like 50 percent of their breeding sites,” says Emily Mowat, a BirdLife woodland birds expert. “It is pretty easy to get quite despondent looking at those figures. But if we hadn’t had all these programs in place to protect habitat and start captive breeding, the birds would be in a lot more trouble now.”

Still, there’s a collective apprehension at the approaching fire season, which officially begins October 1. In his darker moments, Roderick returns to the energy he felt when setting the captive-bred birds free in June: “Everything about this release is good news.” Weeks afterward, observers had recorded several instances of captive and wild birds feeding on the same trees and visibly interacting. Most exciting was that a wild male had been observed making romantic advances toward two different captive-bred females, perching right next to each and calling to her.

In this way, perhaps volunteer, scientist, and bird are not so different—all trying to navigate their way through an increasingly uncertain world.

This story originally ran in the Fall 2020 issue as “Trial By Fire.” To receive our print magazine, become a member by making a donation today.